Renewable energies, green/blue/bio-economies, waste management systems, as well as sustainable agriculture and aquaculture hold within them the possibility of working towards a “Greater Good”, however, “goodness” is frequently built on toxic colonial and capitalist processes that are rendered invisible through sustainability discourse. How can good practices, relationships, and things be cultivated in an environment where toxicants, toxic politics, and toxic relationalities are constantly reproduced? How do toxic production systems—based on extractivism, colonialism, and plantation capitalism—foment new forms of sustainability that cannot be excised from these deadly foundations?

Category: Themed Collection

Caring for women in a contaminated environment

Located in the Southeast of Mexico (Figure 1), the state of Chiapas is among the top 10 states in pesticides use (Bejarano González 2017). Since 2012, I have been conducting research in Chiapas on women’s reproductive healthcare. I collaborated with the Organization of Indigenous Doctors of the State of Chiapas (OMIECH in Spanish) to document the impact of reproductive health policies on Indigenous midwives’ practices. In rural areas, these women, who have acquired knowledge through their own experience of pregnancy birth and postpartum and/or trained with an older midwife, provide daily care to women and their families. As farmers, they are also acute observers of environmental change.

In May 2019, the town of San Cristóbal de las Casas hosted the First Mexican congress on agroecology. During the opening of the congress, voices in the audience started chanting, “Without feminism, there is no agro-ecology” (Figure 2). The group, made of a dozen women — researchers, activists, students, farmworkers, wanted to draw attention on the intersections between women’s rights and environmental sustainability. Later, during a roundtable, the founder of an “organic and feminist” coffee brand explained, “We need agro-ecology to be a choice for life (opción de vida). There can’t be agroecology if there is machismo, if there is violence, if there isn’t food on the table. Agroecology is a choice for our children’s lives.”

In Mexico, over 180 highly hazardous pesticides component are authorized, including many forbidden by international conventions (Bejarano González 2017). Glyphosate residues have been found in industrial corn tortillas and human bodily fluids. A Tsotsil midwife in her late 30s from a village near San Cristóbal, told me she remembered when as a child her father started using pesticides in the milpa (cornfield). His own father told him to stop, but the damage was already done. “Even though he does not use it anymore, there is contamination everywhere. Everything is contaminated.” When “everything” around is contaminated – by mines, pesticides, corporations – what does caring for one’s family and community look like?

Indigenous women at the crossroads of environmental and reproductive justice

Midwives across the continent position themselves as defenders of women’s right to choose how to give birth and as protectors all forms of life – human and nonhuman (Dennis and Bell 2020). Kichwa environmental activist Elvia Dahua, leader of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon described this relationship in an interview for the Tejiendo Cuerpos Territorios (Weaving Body Territories) platform: “Us women, we are those who work the land. The first who chose the water to drink, to feed the children, the husband. This is why us, we know the value of mother-earth, how we can care for nature, how we can care for the earth, the territory, because the territory is our market, the territory is our pharmacy where we can find ancestral medicine.”[1] To express the intersection in which Indigenous women stand Katsi Cook, Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne midwife, coined the term environmental reproductive justice: “Environmental justice and reproductive justice intersect at the very center of woman’s role in the processes and patterns of continuous creation” (Cook 2007:62).

In Chiapas, Indigenous women have been at the forefront of the defense of the territory (Olivera Bustamante, Cornejo Hernández, and Arellano Nucamendi 2016; Valadez 2014). They draw on their multiple experiences as mothers, midwives, farmers and community leaders to raise awareness on the health and cultural consequences of environmental change. Midwives have a close relationship with their environment, in which they find medicine to cure their patients during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum (Icó Bautista and Daniels 2021). During a meeting of midwives in Mexico, organizations from various countries of Abya Yala[2] shared a statement highlighting the importance of caring for all forms of life. Their discourse interwove the sacredness of birth and Indigenous peoples’ strong connection to the earth: “Caring for the way we are born means defending the sacred link that binds us to the earth […]. We fully trust women and their babies’ embodied knowledge and the strength of mother-earth. This is why we rely on its [natural] elements to maintain balance and put ourselves at the service of life and its cycles” (Consejo de Abuelas Parteras Guardianas del Saber Ancestral de México et al. 2018). Contamination threatens this balance in many ways. One of the forms I have documented in my research is the impact on medicinal plants, which midwives use on a daily basis.

Caring when plants disappear

For thirty-five years, the OMIECH has organized community health workshops in Indigenous communities of the state. The goal of the organization is to strengthen Indigenous medical knowledge. The Women and Midwives Section, coordinated by Micaela Icó Bautista, organizes community workshops focused on pregnancy, birth, postpartum and on common diseases in the communities (Icó Bautista and Daniels 2021). In these workshops, participants share how they cope with common illnesses, by sharing medicinal plant recipes, massage indications and spiritual ceremonies. Knowledge exchanged during workshops is then compiled into booklets that are shared back in the villages.

In 2014-2015, I helped organize some of the workshops. One of them took place in a community in the municipality of Huixtan, where Micaela Icó Bautista and I met with Doña Lupe, a Tseltal midwife in her 50s, and member of OMIECH. When we arrived, we followed the midwife and her son-in-law into the milpa behind the house, where they searched for medicinal plants that would be used as props during the workshop (Figure 3). As soon as the workshop started, participants listed the common diseases of women, men and children in the community. In the second part of the workshop, all were invited to share their knowledge about local remedies.

A few years later, in 2018, Micaela returned to the same village. When I met with her a few months later, she described how, during the workshop, older midwives like Doña Lupe recalled the chikin burro (“donkey’s ear,” a mix between the Tseltal word for ear, chikin, and the Spanish word for donkey, burro) a medicinal plant used during childbirth and postpartum.[3] Younger women were puzzled about the name, and started laughing, not knowing it was a medicinal plant. Micaela reported, “The parteras they said that before there were plenty of this plant, but now it is becoming scarce. In the hills, there are barely any left.”

In the workshop’s minutes, women attributed the disappearance of the chikin burro to a combination of factors, including deforestation linked to the construction of new roads, a shift in agricultural practices (from family-based to industrial), and the use of pesticides. Chikin burro was not the only plant affected, they added, “Plants like epazote, coriander, green tomato… They are disappearing. They used to grow in the milpa and now they don’t anymore, because of the pesticides. It all started 5 years ago, but only now they are realizing that it is hurting the earth.” During the workshop, Doña Lupe poignantly described the consequences of such a loss, saying, “it is like putting an end to part of community life.” The situation in Huixtan is not unique, and across Mexico Indigenous peoples experience how the loss of plants is also a loss of their language (Arriaga-Jimenez, Perez-Diaz, and Pillitteri 2018).

With disappearing plants, and the health impacts of environmental contamination, midwives are confronted to new diseases while their tools to cure are getting scarcer. For María del Carmen, a 38-year-old midwife who lived nearby the town of Comitán, and who started attending births when she was 17, “There have been changes in women’s health because of bad eating habits. Since childhood, they eat Sabritas (chips), candy, ham, cheese… This is not eating! In the past, we ate a lot of mushrooms from the forest. Not anymore. And women, they don’t even listen to us anymore. From there, complications arise: hemorrhage, miscarriage…”

During my work with Micaela Icó Bautista, I noticed the increasing trouble she faced in collecting recipes when editing the boletines; there were each time fewer people to share recipes, as older midwives passed away and some plants were more difficult to find. But she tirelessly asked midwives about their “secrets” (Icó Bautista and Daniels 2021), and encouraged them to start their own medicinal garden, to keep transmitting the knowledge which is essential for the health of women and their families, and the cultural reproduction of Indigenous communities.

Mounia El Kotni (PhD, SUNY Albany 2016) is postdoctoral researcher in anthropology at the Cems-EHESS Paris, and 2019-2021 Fondation de France grantee in environmental health (grant n. 00089806). She has conducted research on maternal health policies in Mexico, and the consequences on traditional midwives’ practices since 2013. Her current research is focused on the gendered politics of environmental contamination and environmental protest in Chiapas. Contact: www.mouniaelkotni.com

References

Arriaga-Jimenez, Alfonsina, Citlali Perez-Diaz, and Sebastian Pillitteri

2018 Ka’ux Mixe Language and Biodiversity Loss in Oaxaca, Mexico. Regions and Cohesion 8(3). Academic OneFile: 127-.

Bejarano González, Fernando, ed.

2017 Los Plaguicidas Altamente Peligrosos En México. Texcoco, Estado de México: Red de Acción sobre Plaguicidas y Alternativas en México, A. C. (RAPAM).

Consejo de Abuelas Parteras Guardianas del Saber Ancestral de México, Consejo de Abuelas Parteras Guardianas del Saber Ancestral de las Américas, Nueve Lunas S.C., Oaxaca, et al.

2018 Pronunciamiento. Foro “Partería, Cultura, Ancestralidad y Derechos”. Oaxaca, México.

Cook, Katsi

2007 “Environmental Justice: Woman Is the First Environment.” In Reproductive Justice Briefing Book; A Primer on Reproductive Justice and Social Change Pp. 62–63. Pro-Choice Public Education Project.

Dennis, Mary Kate, and Finn McLafferty Bell

2020 Indigenous Women, Water Protectors, and Reciprocal Responsibilities. Social Work 65(4): 378–386.

Icó Bautista, Micaela, and Susannah Daniels

2021 OMIECH: Traditional Maya Midwives Protecting Women’s Health. Cultural Survival Quarterly 45(1): 26–27.

https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/omiech-traditional-maya-midwives-protecting-womens-health

Olivera Bustamante, Mercedes, Amaranta Cornejo Hernández, and Mauricio Arellano Nucamendi

2016 Organizaciones campesinas y de mujeres de Chiapas. Movimiento Chiapaneco en Defensa de la Tierra, el Territorio y por el Derecho de las Mujeres a Decidir. Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica.

http://repositorio.cesmeca.mx/handle/11595/877, accessed May 30, 2018.

Valadez, Ana

2014 Saberes Femeninos En El Ámbito Comunitario Campesino. Contrahegemonía, Defensa Del Territorio y Lo Cotidiano En La Lacandona. In Más Allá Del Femenismo. Caminos Para Andar. Márgara Millán, ed. Pp. 145–154. México, D.F: Red de Femenismos Descoloniales.

[1] Interview available at https://youtu.be/pzqkOdb76A4

[2] The Kuna word for territory, used by Indigenous activists to refer to the American continent in a decolonial position.

[3] I was not able to retrieve the Latin name of the plant.

Seeing with Water: Reflections from the InterAsia Water(s) Graduate Conference at Yale University

Rains, rivers, tides, wells—waters, in their multifarious forms, have long shaped social worlds in and across Asia, as indeed in other parts of the globe. As the recent scholarship on its privatization, commodification, and trade, reminds us, water is a vital resource for human life. But it also exceeds such functions. Water mediates, reveals, nurtures, and obstructs social processes, as a site of mobility and immobility, cultural relationships and meanings, as well as political contestation and negotiations.

Ocean Justice

“Where we live, work, and play.” That’s the phrase environmental justice advocates have used for decades to reimagine the dominant meaning of nature. It’s meant to challenge the stubborn conception that the natures worthy of care are limited to unspoiled virgin forests and exotic creatures in the wild. The expression tries to interrupt the unthinking assumption that the environment is where people are not. It reasserts the truism that a human life is as sacred as a clear vista on a high mountain top.

Governance for the Anthropocene Ocean

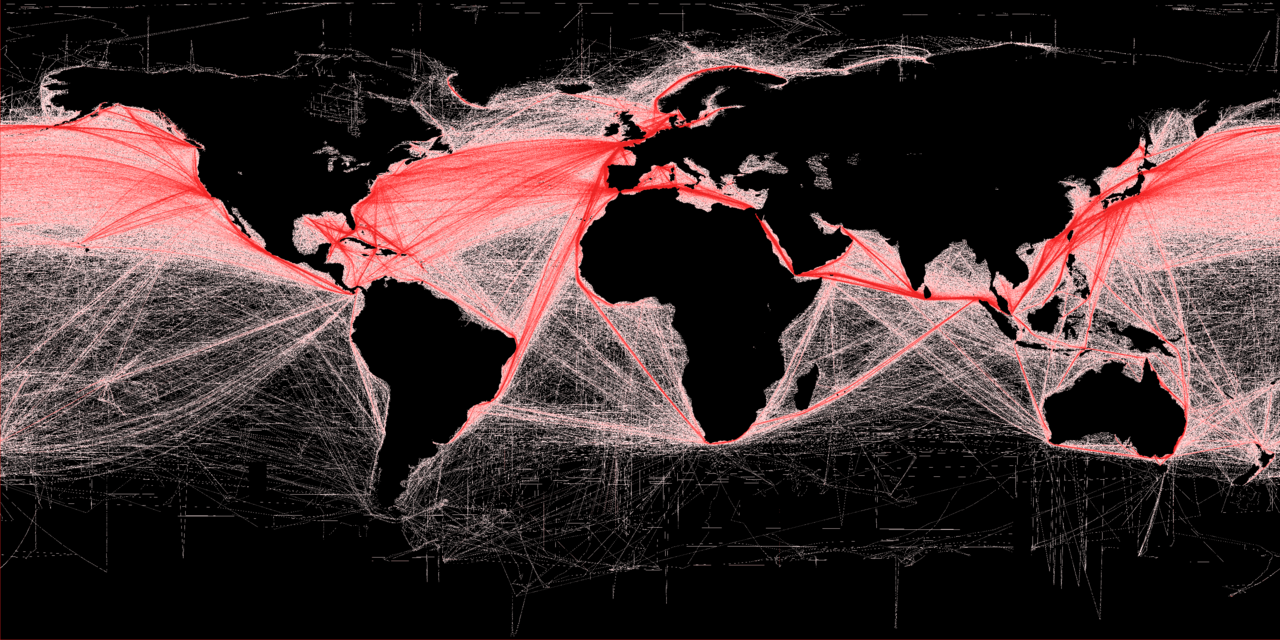

In 2020, the world watched as climate, public health, economic, and racial justice crises converged. It has become increasingly evident that failures of collective and public policies around health and the environment have perpetuated individual suffering. If ever there was an opportunity for the collective to re-think business as usual… it is now. We are firmly situated in the Anthropocene: a time in which human activities are arguably driving our climate and changing environment. The ocean is not exempt from these human influences. Indeed, human energy demands and associated carbon emissions, unsustainable extraction of living and non-living marine resources, land-based activities, and natural processes are contributing to significant changes in marine and coastal environments. These changes include the persistence of plastic waste in most, if not all, ocean ecosystems and species, reduced oxygen and lower pH levels in coastal waters, unprecedented shifts in the range and distribution of marine species, and sustained elevated ocean temperatures over time and space, among others. These conditions exemplify what we are now calling the Anthropocene Ocean. The Anthropocene Ocean is also occurring amidst rapidly changing societies and associated limits to land-based industrial expansion; feeding an emerging narrative about the economic potential of the ocean and its resources (Campbell et al. 2016). Our rapidly changing ocean is also now perceived as the next frontier for growth and expansion of our global economic system.

Fish, Men, and Sea

“More to Sea” is a photojournalism project I engaged in May 2018 to June 2019. This project was an independent project, which was done after I graduated in a marine governance course. I’m currently a PhD student at Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of the University of Technology in Sydney where I study livelihood sustenance of small-scale fishers and local food systems. With More to Sea, I aimed to learn how small-scale fishers were doing. Photographs were combined with fishers’ stories and published on a website (moretosea.nl) and social media. An ebook is about to be launched by Too Big To Ignore, which discusses problems faced by fishers, solutions found, and future scenarios. For the EnviroSociety blog, I have created this short video which shows a number of quotes and photos of fishers that illustrate relations to fishing livelihoods, and people’s knowledges of their environment.

Shifting Baseline and Factish Resilience

The 1949 Fisheries Law in Japan underwent a historic revision in 2018, which went into effect in December 2020. The revision included the further application of science-based resource assessment, the introduction of the Individual Quota (IT) system, the expansion of the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) to more commercially targeted species, and the loosening of the entry restrictions to open fisheries to private companies. While the inclusion of scientific knowledge and approaches could deepen our understanding of oceans and marine species in the Anthropocene, most coastal fishing communities in Japan, whose fishing operation is local and cooperative-based, could find this revision a threat to their communal livelihoods due to its emphasis on rationalized single species-oriented approach to management, rather than a relational multi-species approach for their community wellbeing. This short essay aims to supplement and contextualize my recent article in Environment and Society (Hamada 2020) with the current state of Pacific herring fishery in Japan.

Lines in the Water: Thinking about access, tenure, and practice in traditional marine hunting communities

The sun beats down from a muggy, overcast sky. It turns the small hummocks of a calm ocean to a hammered pewter sheet as far as the eye can see. I sit towards the front of the boat with the harpooner’s assistant squinting out at the waters of the Savu Sea. It’s the end of a long hunting day on the water and we will soon call it quits and head home to Lamalera empty-handed after following a pod of sperm whales moving eastwards. We’re the farthest I have been out this season, but as I look north to the island, we are still directly south of the small peninsula of Atadei, on Lembata’s southern coast. At this moment I realize the endurance of Lamalera’s previous generations of marine hunters: as far as we have come, we are nowhere near the edge of the community’s historical hunting range.

Thinking about Ownership of the Sea

The notion of property has had many accolades assigned to it. In some iterations, it is the bringer of freedom (Anderson and Huggins 2003); in others it is a wielder of power (Underkuffler 2003). It is also a way of distinction between culture and nature, boiled down to the ownable and unownable. Land, a cultural prism, has long been an easily divisible and ownable space, whereas the sea, in its distant bubble of “hypernature,” has never been for individual ownership (Helmreich 2011; Jackson 1995). (I speak here of course for our modern Western society; individuals and communities have apportioned and “owned” coastal areas in numerous cultures across centuries [see, e.g., Mulrennan and Scott 2000]).