The Fire

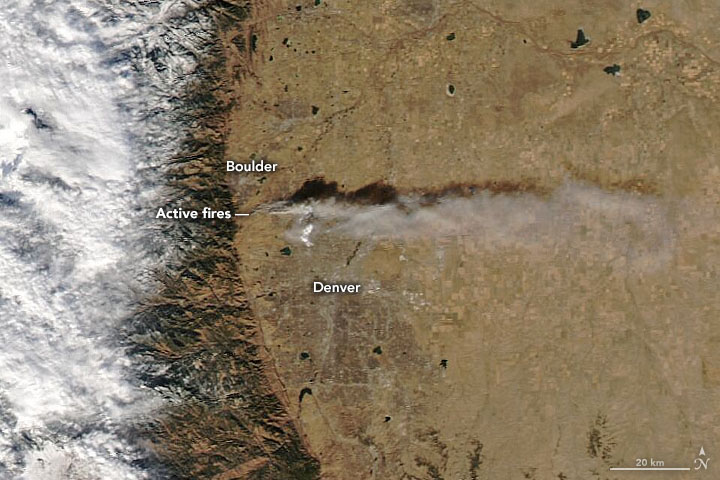

On December 30th, 2021, the Marshall Fire broke out in suburban communities south-east of the idyllic city of Boulder, Colorado, located at the foot of the Rocky Mountains in the United States. Within hours, the fire burned roughly 1,000 homes down to their foundations. It was deemed an “urban fire storm” by climate scientist and Boulder local Daniel Swain.

Our parents’ typical American suburban home was one of the houses lost to the fire in the city of Louisville. While the location of Colorado’s Front Range in a semi-arid climactic zone already makes it prone to fires, the return of the urban fire storm, as Daniel Swain explains, may become a salient feature – the new normal – of our climate-changed future. In this article, we highlight how the fallout from the fire points to a key challenge – a paradox – standing in the way of genuine sustainable development in America’s suburbia, home to more than half the country’s population.

The Fallout

In the aftermath of the fire, the systematic underinsurance of individual properties has come to light. Faced with this realization, Louisville fire victims were forced to pressure the city council through numerous meetings and a public protest for financial support to re-build their homes. These residents demand subsidies in order to rebuild according to the mandatory but costly 2021 net-zero building codes – the most stringent building codes in the state of Colorado – or, alternatively, request to opt out of these codes altogether. For many, there is no alternative to rebuilding, despite the systematic underinsurance of destroyed properties. Many of the victims are close to retirement age and are planning to retire in the neighborhoods they call home.

The Paradox – Greening American Suburban Communities

To proponents of net-zero housing, enabling fire victims to opt out of the 2021 code would undermine Louisville’s “green” ambitions. But are net-zero, suburban, single-family homes really the answer to the climate crisis? While retrofitting could play an important role in reducing the energy demands of suburban life, the assumption that net-zero building standards pave a pathway towards a green, suburban American lifestyle overlooks how energy-intensive this lifestyle really is.

American suburbia is comprised of predominantly white, middle-class residents living in large, energy-intensive, single-family homes. A substantial portion of suburbanites’ energy demands stems from their car-dependent lifestyle, which includes daily commuting to work and school, shopping, or many leisure activities [1]. Most suburban communities are located in public transportation deserts and frequently lack substantial sidewalk and cycling infrastructure [2]. There is now clear evidence that the vast energy demands of the American lifestyle in general, and suburbia in particular, fuel climate change [3]. Moreover, emissions from suburban sprawl cancel out CO2 emissions savings from denser urban centers [4].

While energy-saving technology (such as retrofitting, high-performance windows, high-efficiency heating and cooling systems) does not fundamentally change the ways people live, move, and work in suburban America, it can act as a fix that allows homeowners and the housing industry to continue business as usual: homeowners living in energy efficient homes save some money through lower energy bills, and their homes increase in value. Some of the savings on energy bills are spent for installations and maintenance of the energy-saving technology, which generates a new market for installations, updates and repairs. At first glance, everyone seems to benefit [5].

However, in order to produce enough renewable energy to supply electricity to single-family homes, the City of Louisville would need to build its own solar farm [6]. While solar power reduces reliance on fossil fuels, this raises the question of how renewable energy should be used: should renewable energy power the status quo of single-family homes in suburban public transport deserts? Or should we rather use solar energy to power a different kind of living? Given the limited supply of renewable energy, and in light of considerable socio-ecological costs associated with renewable energy production [7], it would arguably be more sustainable to invest in dense urban environments composed of multi-family retrofitted and fully-electrified houses close to public transport [8].

Undoing the Paradox?

A city that is serious about its net-zero pursuits would need to put the onus not just on individual property owners who now face difficult decisions about rebuilding or moving elsewhere. A genuine net-zero strategy at the city level would have to be centered around different urban planning and housing development altogether. Aside from the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, climate policies would also need to address environmental and social justice issues in order to redress a history of exclusionary and racialized urban planning, development, and zoning practices, which have produced energy-intensive suburban landscapes and lifestyles in the first place. This history is deeply entangled with issues of affordability and diversity, and the availability of jobs, education opportunities, and public transport infrastructure.

Planning with environmental justice in mind would require new policies and funding earmarked for densification-centered, (sub)urban development powered by alternative forms of energy with an emphasis on walkability, public transport, and green and blue spaces that meet social needs and ecological goals at the same time [9]. To be sure, the Federal Government’s 2021 infrastructure and “Build Back” bills echo these needs and goals. However, the Federal Government lacks legal control over how these investments are spent at the state and city levels. Without active citizen engagement through accountability panels and environmental justice oversight committees, there is a real risk that states will spend federal money on projects that may undermine progressive climate policies while further entrenching environmental injustice through suburban housing and transport planning [10].

Epilogue

While Marshall Fire victims are busy with planning to rebuild despite systematic underinsurance and new building codes, the difficult question as to how to transform the American landscape of suburban single-family housing into socially and environmentally more just ways of living together remains unaddressed. It seems to us that a genuinely sustainable housing building code must go beyond retrofitting and electrifying single-family suburban housing according to the latest environmental standards. Climate-proof, sustainable housing has to address several interconnected challenges all at once: suburbanization and densification; issues of race, class and diversity; commuting and public transport; but also income inequality and retirement. If these issues remain unaddressed, we fear that urban and housing development will continue in a maladaptive fashion, building and rebuilding the same types of communities that contribute to and are prone to climate-related environmental disasters, while expecting different results.

Stephanie Loveless is a PhD student at the section for Cultural and Social Geography at Humboldt University (Berlin, Germany). Stephanie’s research focuses on the right to the city by examining the role of social movements and residents groups in the creation of public (green) spaces through urban renewal projects. She also works for Stay Grounded as a press and communication campaigner.

Contact: loveless@huberlin.de Twitter: https://twitter.com/Steph_Loveless

Jevgeniy Bluwstein is a Lecturer in Human Geography at University of Fribourg (Fribourg, Switzerland). Jevgeniy has published extensively on conservation-, development-, and socio-ecological transformation-related aspects in journals such as Geoforum, World Development, Journal of Agrarian Change, Journal of Political Ecology, and Political Geography. Contact: jevgeniy.bluwstein@unifr.ch Twitter: https://twitter.com/jevgeniy_b

References

[1] Daniel, Thomas L., 2021. “Re-designing America’s suburbs for the age of climate change and pandemics”. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 3, 225-236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-021-00084-5.; Teicher, Hannah M., Phillips, Carly A. & Todd, Devin, 2021. “Climate solutions to meet the suburban surge: leveraging COVID-19 recovery to enhance suburban climate governance”. Climate Policy, 21:10, 1318-1327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.1949259

[2] Daniel, 2021.

[3] Daniel, 2021.; Mitchell et al, 2018. “Long-term urban carbon dioxide observations reveal spatial and temporal dynamics related to urban characteristics and growth”. PNAS, 115 (12). pp. 2912-2917. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1702393115.

[4] Jones, Christopher and Kammen, Daniel M., 2014. “Spatial Distribution of U.S. Household Carbon Footprints Reveals Suburbanization Undermines Greenhouse Gas Benefits of Urban Population Density”. Environmental Science & Technology., 48 (2), 895-902 DOI: 10.1021/es4034364.

[5] Knuth, S., 2019. “Cities and planetary repair: the problem with climate retro-fittting”., Environment and planning A: economy and space., 51 (2). pp. 487-504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518×18793973.

[6] Marshall Fire neighborhood disaster recovery group meetings, email exchanges and informal discussions with individuals from December 30, 2021- March 30, 2022.

[7] Sultana, Farhana, 2021. “Critical Climate Justice”. The Geographical Journal, 188 (2). https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12417; Zografos, Christos and Robbins, Paul, 2020. “Green Sacrifice Zones, or Why a Green New Deal Cannot Ignore the Costs Shifts of Just Transitions. One Earth commentary”. Volume 2 (5), p.543-546, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.10.012.

[8] IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J.Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. DOI: 10.1017/9781009157926.

[9] IPCC, 2022; Teicher et al, 2021.

[10] Daniel, 2021.; Rothstein R, 2017. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York, NY: WW Norton.; Haase, Dagmar et al, 2017. “Greening cities e To be socially inclusive? About the alleged paradox of society and ecology in cities.” Habitat International 64 (2017) 41-48.; Shokry, Galia; Connolly, James JT; Anguelovski, Isabelle, 2020. “Understanding climate gentrification and shifting landscapes of protection and vulnerability in green resilient Philadelphia”. Urban Climate, 31.; Keenan, Jesse M; Hill, Thomas and Gumber, Anurag, 2018. “Climate gentrification: from theory to empiricism in Miami-Dade County, Florida”. Environmental Research Letters., 13. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aabb32