In our everyday lives we encounter and are exposed to a dizzying array of chemicals – through the air we breathe, water we drink, food we eat, products we buy, work we do, and environments we move through. A recent review of the scientific literature estimates that the accelerating mass-production of chemicals has led to the accumulation of 350,000 “novel entities” (human-made chemicals that did not previously exist) in the environment.[1] They suggest this exceeds the “planetary boundary” for chemical pollution, meaning it is and will continue to disrupt the operation of ecological systems and have major impacts on human health.

While these exposures and the resulting health effects are undoubtably experienced unevenly, the mass-produced chemicals dispersed in the environment have led to “near universal human exposure”.[2] Accordingly, we suggest reframing the problem of chemical exposure from a concern with the toxicity of individual chemicals to considering and acting upon cumulative toxicities. However, if the adverse effects of toxicity are not simply a property or result of individual toxic chemicals and exposure pathways, this raises a number of existential and epistemological questions. What kinds of knowledge are needed to grasp cumulative toxicity? How can we shift our attention and object of inquiry from single chemicals to cumulative toxicities? How can cumulative toxicities be mitigated and regulated?

In this essay we focus on the problem of sensing cumulative toxicities. Drawing together some of the scholarship presented at a series of panels we hosted at the 4S Annual Meeting in 2021[3], we begin charting an approach for understanding and acting upon the cumulative toxicity of everyday life through the investigation of sites of sensing in which multiple kinds of knowledge are brought together. In this way, we position embodied practices that sense and make sense of cumulative toxicities at the intersection of producing knowledge and enacting regulation. Focusing on sites of sensing draws attention to the scales at which cumulative toxicities emerge and how knowledge about their adverse health impacts is always embodied, partial, and situated.

What makes cumulative toxicities so difficult to sense?

Across the panels, scholars emphasized the multi-scalar nature of cumulative toxicities, emphasizing how pollutants and other chemicals cross boundaries and disrupt scalar categories of all kinds – bodily, spatial, and temporal.

Raúl Acosta, bringing together anthropology and urban political ecology, suggests we can better grasp the dynamism of chemical presence and effects by conceptualizing these molecular entities as metabolic flows that interconnect cities, countryside, bodies, economies, and ecologies. He draws attention to how microscopic metabolic flows produce “chemoscapes” characterized by uneven distributions of chemicals in landscapes and bodies.

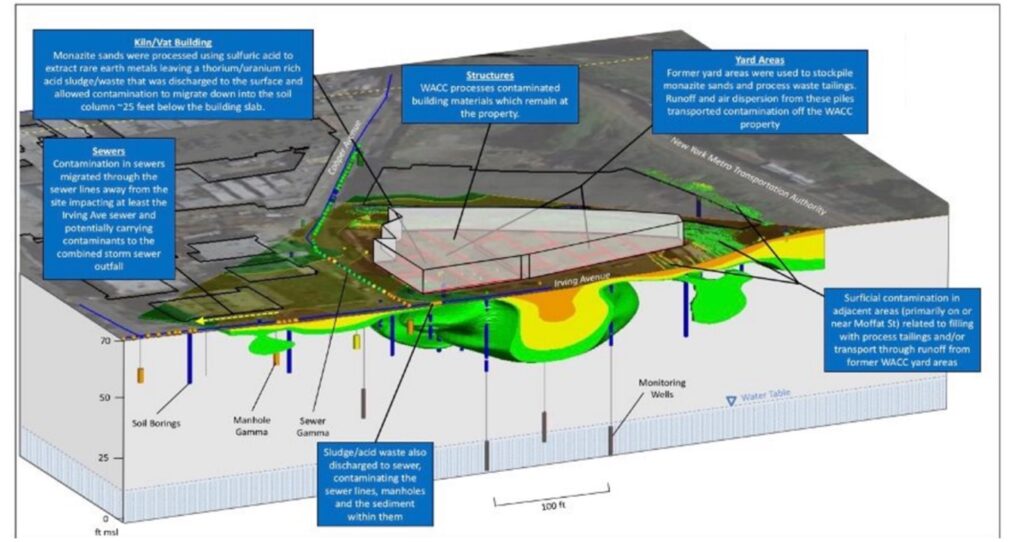

Similarly, Henry Osman describes the emergence of a “nuclear landscape” at an abandoned factory in Brooklyn, NY that once processed monazite sands from the Belgian Congo, producing a radioactive toxic sludge as waste. However, the accumulated toxic sludge was considered insufficiently radioactive, making remedial actions legally unnecessary until 2014. Acosta would describe this as a failure of “technomolecular governance” – the power-laden relations between a variety of stakeholders – which too often serves as a tool to advance private interests instead of as an exercise seeking the inclusion and consideration of diverse stakeholders in the service of the public good. While the “nuclear relations” of irradiated land include how radioactive material acts upon and marks bodies for increased risk, Osman points out that long-term exposure is often accompanied by an absence of sensory input and somatic apprehension. The compounded invisibility of microscale chemicals, macroscale socioeconomic structures, and long-term quotidian exposure can make cumulative toxicities a challenge to sense, be made sense of, and, in turn, acknowledged by those exposed, scientists, and policymakers.

Sites of Sensing

As papers across the panels emphasized, cumulative toxicity is lived through long-term exposure. Environmental exposure to specific classes of toxic chemicals can affect the function of endocrine, respiratory, nervous, and immune systems across multiple generations. Furthermore, exposure to toxic chemicals is uneven, with marginalized communities suffering higher exposure rates. This temporality and the uneven territoriality of cumulative toxicity is experienced as a kind of “slow violence.”[4] However, just as bodies are unevenly exposed to cumulative toxicities, bodies have disparate experiences and responses to exposure. We suggest that one way to grasp the slow violence of cumulative toxicities is to pay attention to how bodies become attuned to the harms of cumulative toxicities at particular sites of sensing.

Liza Grandia argues that bodies with multiple chemical sensitivity can act as “canaries in the mineshaft of the Anthropocene” that offer warnings about the planetary crisis of “toxic modernity.” Similarly, polluted communities may perceive toxicity in intuitive and sensorial ways. These canaries have much to teach, both epistemologically and epidemiologically. Grandia proposes “canary science” as a way to take seriously the embodied knowledges of those who are most sensitive to the adverse effects of cumulative toxicities. Canaries are not only (sacrificed) sentinels, but whistleblowers and informants that can sing (even canaries in a cage have agency and voice).

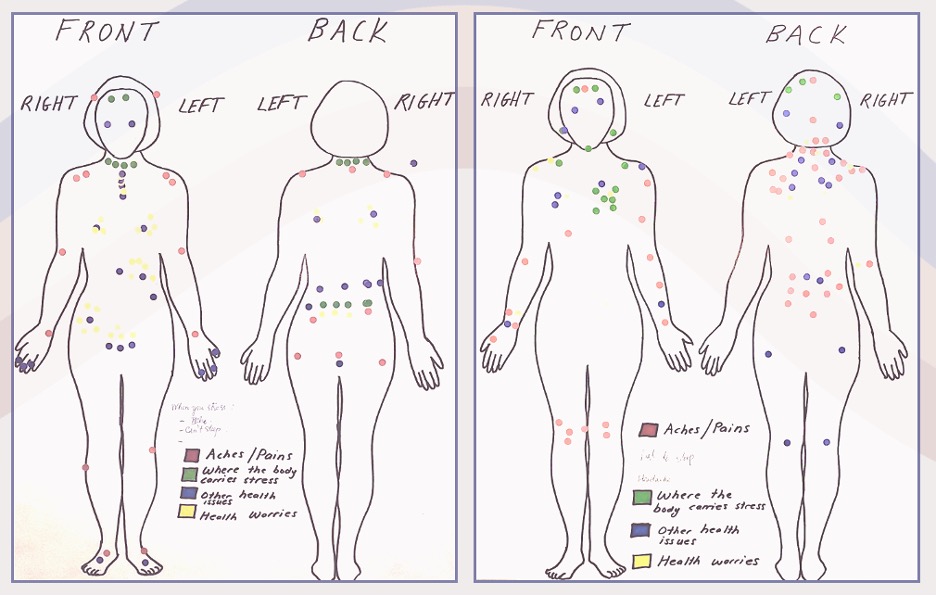

One method for developing, valorizing, and acting upon “canary science” might be mapping the harms of cumulative toxicities. Reena Shadaan worked with nail technicians in Ontario who report a variety of respiratory, dermatological, and other health concerns. Nail technicians are largely comprised of immigrant women of color, whose experiences and health concerns are routinely marginalized and dismissed by medical professionals, policymakers, and the general public. Shadaan engages with occupational health mapping, combining body-mapping and hazard-mapping as a worker-centered method for identifying workplace hazards and health implications. This produces counter-narratives that assert worker embodied occupational hazards, bringing marginalized knowledge and epistemologies to the fore. The cumulative toxicities nail technicians made visible through mapping exercises included the harms of workplace verbal abuse as much as those of chemical toxins. In response to these hazards, Shadaan argues, nail technicians resist at multiple scales: molecular, interpersonal, and collective.

Mayra Sánchez Barba works with another community of canaries— farm-working women— exploring how they learn to touch toxicities through pesticide trainings. Pesticide exposure and worker exploitation, acutely racialized and gendered, result in Latino farmworkers experiencing high rates of health issues, disabilities, and death. However, the failure of regulatory agencies essentially guarantees continued exposure to toxic pesticides. Pesticide residues drift and linger through landscapes – beyond fields, including entering worker homes. Sánchez Barba reveals how coming to understand toxicity through touch facilitates embodied and tactful ways to attend to and approach the slow violence of toxic ecologies. For example, workshop participants pass around an apple with fluorescent powder followed by a baby doll, then with a black light the invisible powder is made visible, with residue on their skin and clothes. Shadaan and Sánchez Barba’s work is about co-producing knowledge about the harms and pervasiveness of cumulative toxicity – recognizing, cultivating, and valorizing epistemologies from below.

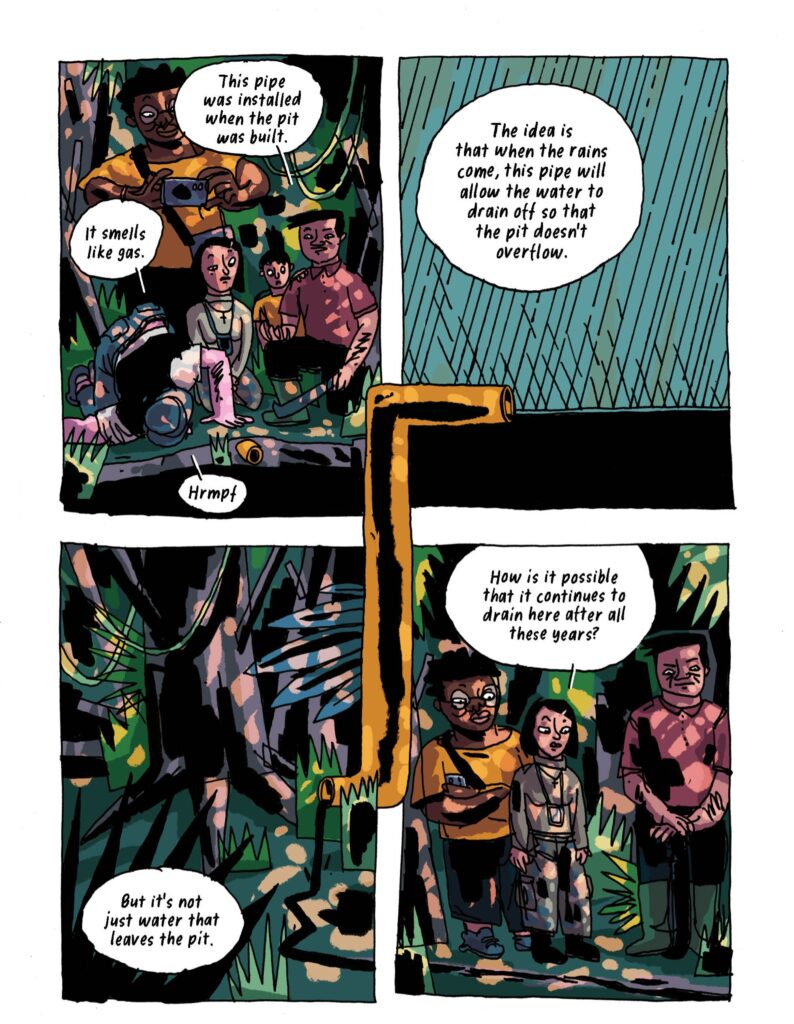

Sensorial engagement is not only for those most exposed and affected by cumulative toxicities. As Amelia Fiske explores ethnographically and through the creation of a graphic novel (co-created with Jonas Fischer), on toxic tours in the Ecuadorian Amazon, ‘tourists’ who may be (or perceive themselves to be) far removed from the violent history of oil extraction confront it up close. Since the 1960s, oil operations, joint venture between Ecuadorian state and Texaco, led to widespread dumping of crude oil and production liquids into local waterways while burning of byproducts resulting in massive environmental contamination. Indigenous and peasant farming communities experienced environmental, health, and cultural damages. Toxic tours proceed from telling participants they are standing on a waste pit to pulling up toxic soils with an auger and inviting participants to engage the sample with gloved fingers, noses, and mouths. More than simply visiting and discussing toxicities, through sensory engagements participants experience, come to know, and are enrolled in toxic environments.

Conclusion

Cumulative toxicities are multi-scalar, from global to microscopic flows, as are the impacts, both in terms of planetary boundary and individual health. Importantly, this destabilizes static scalar categories themselves – the planetary can be found within the individual, and microscopic entities travel globally. Thus far, both the (limited) scientific knowledge establishing chemical toxicity and the (insufficient) regulatory measures enacted have largely focused on single chemicals, single exposure pathways, and single species; meaning both knowledge and regulation addressing the toxicities that emerge through copious, interacting chemicals is sorely lacking. Furthermore, there is a tension between that which can be sensed and the innumerable chemicals, exposures, and toxicities that cannot so easily be made sense-able. To make cumulative toxicities actionable, researchers, activists, and policymakers must address this tension.

[1] Persson, L., Almroth, B., Collins, C., et al. (2022). “Outside the Safe Operating Space of the Planetary Boundary for Novel Entities.” Environ. Sci. Technol 56: 1510−1521.

[2] Landrigan, P., Fuller, R., Acosta, N., et al. (2018). “Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health.” The Lancet 391: 46.

[3] The four panels were titled: “Systematic entanglements”, “Risky engagements”, “Making toxicity visible”, and “Feminist and queer approaches to the toxic”.

[4] Nixon, Rob. (2011). Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Anita Hardon is a professor of knowledge, technology and innovation at Wageningen University. Trained as a medical biologist and anthropologist, she engages in multi-level, multi-sited, and often interdisciplinary studies on pharmaceuticals, immunization, new reproductive technologies, and AIDS medicines. Her most recent book, published open access with Palgrave, is Chemical Youth: Navigating Uncertainty in Search of the Good Life (2021).

Tait Mandler is an interdisciplinary academic currently completing a PhD in Anthropology and Urban Planning at the University of Amsterdam. Their research interests include urban political ecology, agri-food economies, human-chemical entanglements, and anthropology of the senses. They have a forthcoming edited volume, Turning Up The Heat: Urban Political Ecology for a Climate Emergency, with Manchester University Press.