A disaster is said to be a social construct because its sudden occurrence disrupts the functioning of a society, causing human, material, economic, cultural and environmental losses that exceed the community’s ability to cope using its own resources. Thus, any natural hazard that leads to loss of human lives and property and damages the surrounding resources and non-human entities can be called a disaster (Wisner et al, 2014; Nadiruzzamam, 2016).

Historical evidence has shown that the region of Sundarbans has faced cyclones and their never-ending fury through time. The oldest recorded evidence is from 1582 AD, when a cyclone swept over Bakergunje, in Bangladesh’s Barishal district (part of Bangladesh Sundarbans), causing a loss of 200,000 lives, hectares of farmland, and many cattle. O’ Malley, in his Gazetteer of 24 Parganas (1914), asserts that there is “no safeguarding against the sudden fury of a cyclone, and its record shows that, though they occur at irregular intervals, these violent storms are far more destructive of life and property than either droughts or floods” (Biswas, 2020).

In the last three to four years (from 2019 to the present) Sundarbans faced five major cyclonic events, ranging from ‘extremely severe’ to ‘super cyclone’. They took place in a period of almost six months. If the tropical and local storm surges are also considered, the count goes up to nearly 15 events in just three years.

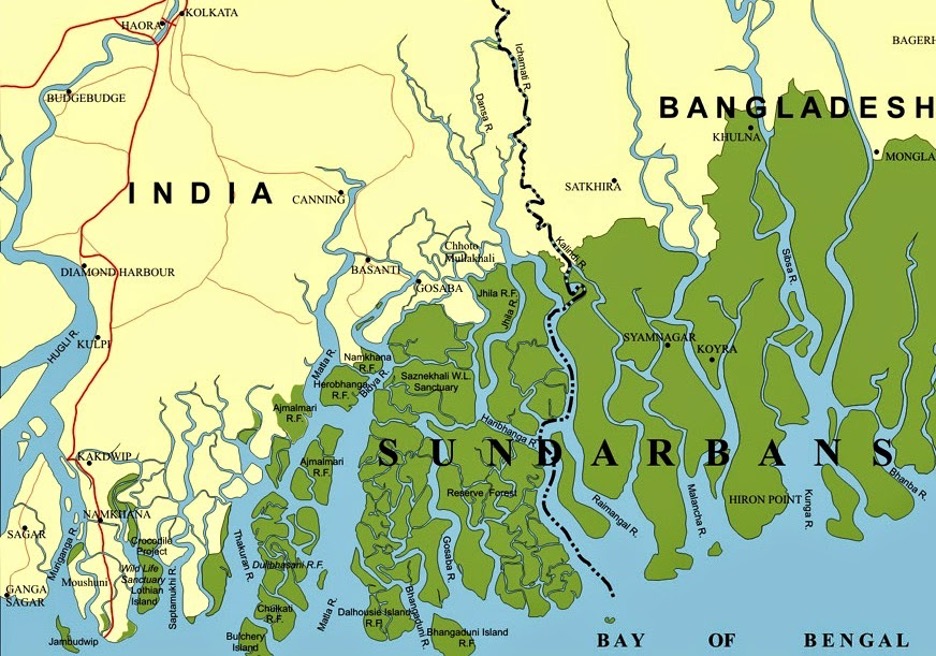

The area of Sundarbans is similar to an archipelago, comprising 102 islands, of which 54 are inhabited by people, while the rest of the area is covered by forests (Dey, 2019). People living here belong to the most socially disadvantaged communities in India and Bangladesh, like the Dalits, Adivasis, and religious minorities. The catastrophes hit these areas especially hard, triggering hundreds of thousands of deaths and leading to extreme suffering and the disruption of the daily livelihoods of the communities that are dependent on the landscape and the mangrove forest. Every time the Sundarbans are hit by a cyclone, most of its embankments (locally called Bandh) crack, collapse, and sometimes wash away, leading to post-cyclone flooding. Even during full-moon high tides, the embankments get damaged, and the sea water enters areas of human habitation, causing severe damage to agricultural fields.

The landscape’s soil fertility and productivity have suffered due to the area’s prolonged interaction with cyclones and flooding. This creates questions around the construction and management of embankments: Although government reports and scholarships show that Sundarban villages have been provided with concrete dams, especially after the complete submergence of villages post Cyclone Aila of 2009, these embankments proved to be a failure in the long run. This failure points to problems in design and implementation, which are not in tune with the local ecology and made mostly without consulting the locals (Himalmag, 2020).

In my seven months of fieldwork at two of the fringe villages of Indian Sundarbans, I saw less evidence of embankments still standing, but many remaining patchworks. After several inquiries, I found that locals had been repairing the broken embankments each time a cyclone or flood hit them. The villages illustrated a series of alternative and quick-fix solutions to the embankment breakage and leakage, as shown below in Figures 2 and 3:

Figures 2 and 3 show how the embankment that separates the land from water has been repaired by placing sacks filled with sand and soil over a large tarpaulin or plastic sheet spread across the platform. This is done to prevent the seepage of high tide water from the ruptured spots into the village. Every individual living in the village— irrespective of caste, class and religion— comes together to help. Some would dig the soil to make the barricade more vertical and taller so that the water doesn’t spill over, while others would hold on tightly to the black or white sheets, as shown in the pictures, and pin them tightly with bamboo logs to avoid seepages. All this is done while the cyclone is taking its course.

This sense of community collectiveness and camaraderie can be studied from the lens of resilience. Resilience is all about being able to cope in unexpected or challenging circumstances: it reflects the ability to survive in the face of challenges, overcome barriers and bounce back after setbacks. It also involves learning from those setbacks to better deal with them next time (IRFC, 2012 in Ahmed et al 2016). This continuous cycle of failure-and-success in localized embankment construction and repairment has led the local government to support traditional methods of erosion prevention, so that the embankments can withstand tidal surges or cyclones. Figures 4 and 5 show some of the locally- initiated and conceived structures of safeguarding the island-shores, which are sustainable and generate the local economy by using local products. These are made up of bamboo and endemic plant leaves and tree bark instead of cement and cinders.

Photo by author.

Photo by author.

One of my interviewers, who has faced several cyclones and has actively participated in safeguarding their village from the breakage of embankments, says that earthen- and bamboo-centric embankment protection is more effective than cement-based methods. All they require are some technical improvements. He also adds that a longtime solution like a modernized dam bears high installing and maintenance cost and might not be possible due to the peculiarity and shifting nature of Sundarbans’ landscape. It needs an alternative of little initial cost but regular maintenance and quick forms of repairment. Another striking feature of these localized structures is that locals have planted mangroves alongside the earthen dams, which help cut down the intensity of the disaster impacts.

Facing a cyclone and its consequences has become a part of people’s lives in Sundarbans. From an outside perspective, we might see the severity of cyclone impacts as an indicator of the instability and precarity** of this region’s society. Still, the level to which people have become accustomed to these continuous disasters shows that resilience has complicated the relationship between landscape degradation and marginalization. Acts of resilience have become an emblem of Sundarbans identity, showing the strength and collectiveness of Sundarbans’ people as climate disaster warriors.

References

Ahmed, B., Kelman, I., Fehr, H. K., & Saha, M. (2016). Community resilience to cyclone disasters in coastal Bangladesh. Sustainability, 8(8), 805.

Biswas, C.(2020). “The Aftermath of cyclone Amphan in Sundarbans’, in Countercurrents.org, June 6, 2020. Retrieved from https://countercurrents.org/2020/06/the-aftermath-of-cyclone-amphan-in- sundarbans/

Dey, P (2019). Sundarbans and it many facts. Times of India Travel. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/travel/destinations/sundarbans-which-is-10-times-bigger-than-the-city-of-venice-and-its-many-facts/as67383231.cms

Himalmag Podcast ( June,2020, What the Sundarvan tells us-Interview with Megnaa Mehtta on the Sundarban after Cyclone Amphan. Retrived from https://www.himalmag.com/what-the-sundarban-tells-us-podcast-2020/

Nadiruzzaman, M. D. (2012). Cyclone Sidr and its aftermath: everyday life, power and marginality (Doctoral dissertation, Durham University).

O’Malley, L. S. S. (1914). Bengal District Gazetteers: 24-Parganas. Bengal Secretariat Book Depot, Calcutta.

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2014). At risk: natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters. Routledge.

N.A. Resilience v adaptability. https://blog.innerdrive.co.uk/resilience-v-adaptability

Camellia Biswas is a doctoral student from the Humanities and Social Sciences disciplines at the Indian Institute of Technology in Gandhinagar, India. Her doctoral research focuses on Human-Nature interactions in the Indian Sundarbans from the lens of political ecology under the larger discourse of climate disaster.