All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

Marx and Engel, the Communist Manifesto

When my world evaporated into exhaustion with Long Covid, I found myself pondering Marshall Berman’s (1988) insight from his eponymous book, “To be modern is to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world—and at the same time, that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are” (15). While modernity brought exhilarating emancipation of education, movement, and identity, it also eroded collective safety nets. Albeit “freed” from the constraints of custom, individuals became vulnerable in new ways to accidents, crashes, hazards, or disasters—be they natural, technological, economic. . . or viral. As public health authorities unfurled confusing, if not erratic, directives about mask mandates and vaccination priorities over the last two years, we learned once again how utterly dependent our lives are to opaque bureaucratic institutions and a standardized “utopia of rules” (Graeber 2015). In these contexts, things tend to fall apart (Achebe 1959).

Suffice it to say that, having already been that one in a million to be diagnosed with a stage III cancer before 35, I entered the pandemic with a lower tolerance for risk than most people. Chemotherapy also left me with a petri dish of an immune system.

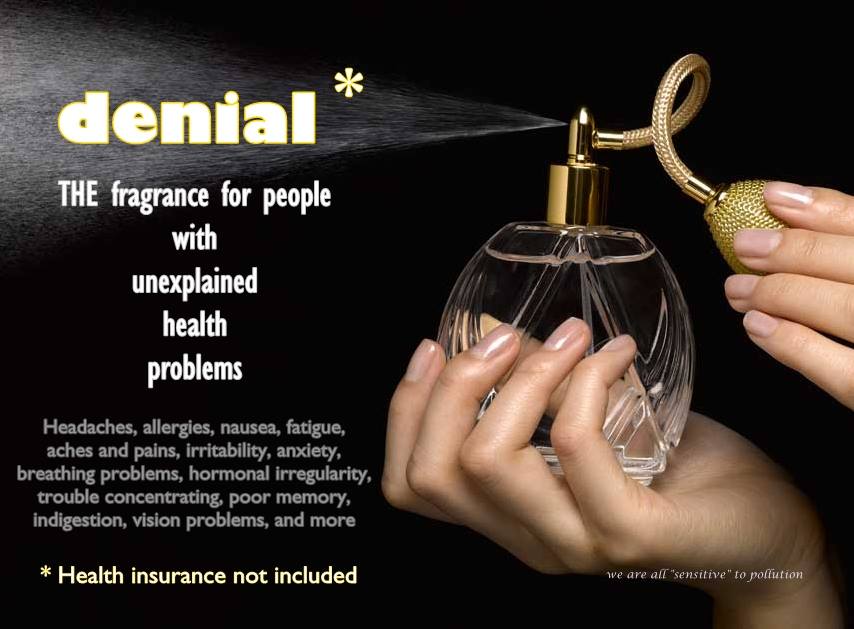

So after reading reports about the viral outbreak in Wuhan in the New York Times, I researched the herbal medicines that TCM doctors were using on the ground and ordered myself some bottles on February 29, 2020 “just in case.” Long before Covid made them politically correct, I already owned a collection of multi-layered, charcoal-activated masks to filter out the petrochemical stench of other peoples’ synthetic fragrances in crowded places like airplanes and theaters. Being chemically intolerant, I hadn’t entered a big box store in a decade and rarely ate out. With my farmbox subscription, a full pantry of delivered dry goods, plus a thriving garden, I was more prepared than others (and introvertedly delighted) to stay home in my fragrance-free abode for however long the lockdown might last.

Yet, no divorced mother is an island. Although I didn’t leave my house for three weeks, Covid came for me on March 31, 2020, before testing— much less any treatment— was available. The week before I had worked myself to the bone to pivot my spring courses online. University administrators were sending professors daily directives to “keep teaching.” They gave themselves and every other member of the university staff an extra allotment of sixteen days of medical leave for COVID-related illness, but not a day for faculty. So, I kept teaching and emotionally laboring to support students in crisis. I had previously worked through dengue fever and malaria multiple times, but always rebounded. Not this time. Two weeks went by, and I remember my horror when someone said they heard it might last six weeks. I somehow got through the 10-week quarter without any teaching relief. Luckily I did not then know that the soul-crushing fatigue would last almost two years.

Canaries to our own rescue

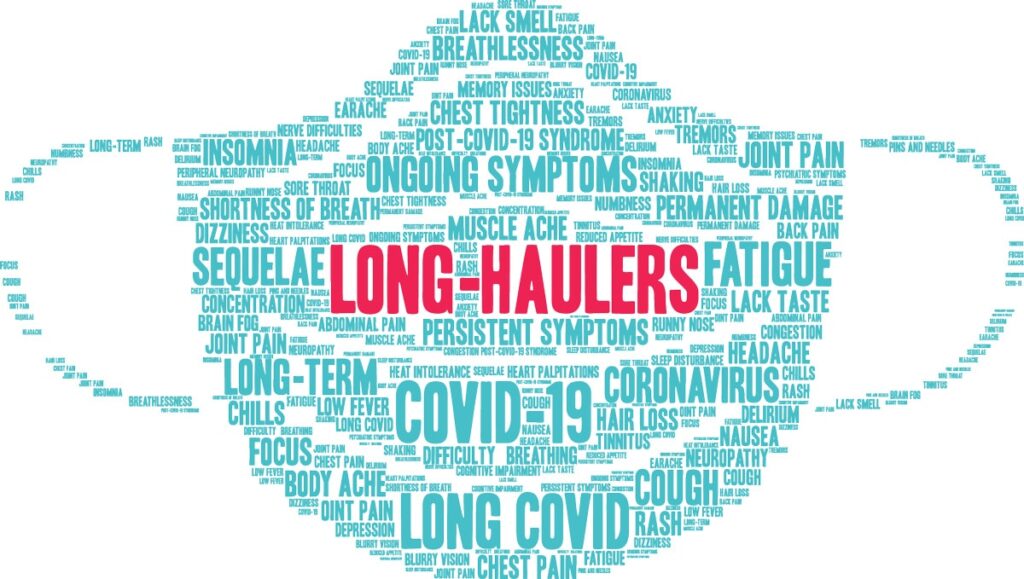

Through profound exhaustion, the “long haul” community organized to support one another. NYC community organizers from a small feminist nonprofit, The Body Politic— who fell ill themselves in the first wave— had the wherewithal to organize a Slack group. Those Slack subchannels remain the best source of experiential information and emotional camaraderie. Other savvy volunteer Facebook administrators organized cohorts by onset of illness, so as the months wore on, we were able to compare and identify a progression of symptoms (e.g. hair loss at month three) without diluting our discussion by having to orient panicked newbies about how to read an oximeter. Heroic spokespeople for the ME/CFS (myalgic encephalitis/chronic fatigue syndrome) movement of “millions missing,” like Jennifer Brea, rallied energy to warn the Long Haulers that we could not exercise our way out of the fatigue. We also owe a great debt to journalists like Ed Yong of The Atlantic who began reporting on the Long Haulers as early as June 2020.

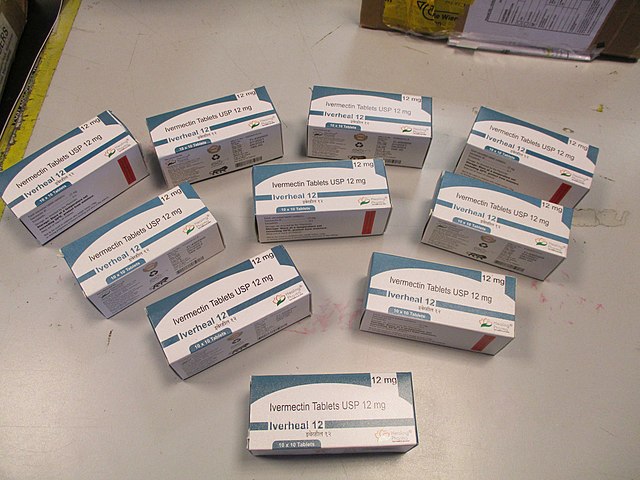

Every other step towards recovery came from a patient recommendation or creative clinicians in the developing world. Knowing their patients will never be able to afford the antivirals that Big Pharma may concoct, doctors in impoverished countries have been far more entrepreneurial in trying to repurpose affordable medicines in their arsenal. By April 2020, researchers in Iraq, Bangladesh, Spain, and beyond were already evaluating the efficacy of ivermectin. I presented copies of these clinical trials to my own doctors and became the first person in my town (or at least the first client of the pharmacy) to receive a prescription of ivermectin in August 2020. By 2021, however, bureaucrats were threatening doctors in the system with disciplinary action should they continue prescribing this effective drug simply because some Fox News viewers poisoned themselves by self-administering veterinary ivermectin (available over-the-counter). However, human ivermectin has been used around the world since 1975 and appears in the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines. Moreover, the researchers who discovered this anthelmintic (de-worming) drug won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2015! The sanctimonious ridicule of ivermectin that unfolded in the news and social media in late 2021 struck me as the worst kind of First World arrogance and privilege.

With the improvement that came with ivermectin, I managed to write an ode to “canary science” for this volume in Environment and Society in which I theorize vulnerability as a key metaphor for times like this pandemic when “all that is solid melts into air.” As Felicity Callard and Elisa Perego noted in a paper that came out concurrent to mine, “Patients collectively made long Covid.” They organized to do their own research through the Patient-Led Research Collaborative. As another Long Hauler eloquently summed up in a recent discussion on Slack: “I want to say I am very proud to be part of this brilliant long covid community. I feel like we’ve collectively figured out a huge chunk of long covid puzzle, and it’s due in large part to an organized patient population advocating for themselves, sharing resources, and working with open-minded, creative doctors (who are sometimes also patients themselves) who are willing to spend time with their patients and really figure out what this condition is all about. A bit of a bright spot in a year that hasn’t always reflects the positive aspects of human nature.”

For certain, had so many doctors and epidemiological luminaries like Peter Piot or Paul Garner and journalists like Morgan Stephens not also fallen ill with Covid in the first wave, we surely would have been dismissed as psychosomatically ill and discarded by the medical system like so many other chronically ill folk. We were also fortunate that Long Covid randomly struck marathoners and other physically active people who even the most neoliberal health system could not blame for not exercising enough. Having myself been medically gaslighted about the chemical intolerances I developed after cancer, I was heartened by the newfound humility of some (but not all) of my doctors about how little they know about multi-system inflammatory syndromes.

At the same time, a disturbing number of Long Haulers are being told by the doctors their symptoms are psychosomatic. According to a patient-led survey, almost half of Long Haulers are working reduced hours and about a quarter cannot work at all. Although President Biden declared that PASC (the official designation of Long Covid as “post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection”) should be protected by the Americans with Disability Act, Long Haulers are struggling to win accommodations. While health insurance companies are reporting record profits, they have done so by denying millions of people with post-Covid complications the tests, complementary care, and specialist services that we need. A new circle of hell should be opened for Anthem executives who rightly calculated I was too fatigued to appeal my denials.

Long Covid comrades Callard and Perego (2021) forewarned, “The speed of publication of COVID-19 research means epistemic authority rapidly consolidates around particular actors. Crucial leads might be lost as background noise – particularly when made by patients, whose expertise is less frequently validated.” When NIH allocated a stunning $1.15 billion for research into Long Covid, many communities of chronically ill folk rejoiced. This grant bonanza is double-edged. As Ed Yong (2021) noted, “The message seems to be: thanks for everything; academia can take it from here.” By characterizing Long Covid as a unique illness, rather than building on the insights of chronically ill folk with similar symptoms like those with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), many new researchers jumping into the funding frenzy could squander the opportunity to rescue others forsaken by the western medical system. Having had one of his own papers rejected for simply including self-reported patient data, neuroscientist David Putrino at Mount Sinai suggested, “What we really need are well-informed patient researchers sitting with NIH officers reviewing grant” (quoted in Yong 2021).

The few allied researchers who have genuinely consulted Long Haulers are making breakthroughs that could help many different types of canaries in the coal mine. For example, Stanford oncologist Michelle Monje found that Covid and chemo neuro-inflammation share similar patterns of persistently activated microglia. Yale immunologist Akiko Iwasaki has admirably engaged with patients’ social media and published a number of paradigm-shifting papers based on real-time interaction with the Long Haulers. Recognizing patterns of illness with large cohorts sickened by environmental toxicants “natural experimental” data (first responders to the World Trade Center, EPA staff, Gulf War veterans, hurricane survivors sickened by mold and toxic FEMA trailers), allergist Claudia Miller is also mounting a major new project on mast-cell activation as a possible common denominator for chronic illness.

The risky end game

When faced with the impossibility of attending to the multitude of things that could go wrong and the sheer mathematical difficulty of fathoming parts per billion or joules per kilo (Starr 1969), people often fall into paralysis or recklessness. As societal fatigue with Covid sets in, I worry that the revolutionary aperture of the pandemic is closing just as I’m feeling better and can do more than lay in bed streaming Marvel videos. Perhaps Omicron its “milder.” As I noted in the article, Long Covid ought to create Rawlsian discussions about our globalized dilemma of mutual vulnerability.[1] The pandemic “veil,” I would argue is not whether you think you can survive the illness, but whether you can dodge disability. Yet, most of the anti-vaxxers with whom I am acquainted have a pollyannaish confidence in surviving the virus, but seem not to have fully weighed the Russian roulette of prolonged debility.

Mortality from the acute phase of Covid illness does follow some patterns of “pre-existing conditions” and racial/socio-economic disparities, but researchers still have no idea who/how/or why Long Covid clobbers some people and not others. Public health authorities have yet to agree upon an internationally standardized definition of Long Covid onset, much less prevalence data. Estimates for previous variants range in the 10-20 percentile, but as many as 50 percent of those infected report symptoms after six months. Theories range from the microbiome, low zinc and vitamin D levels, prior Epstein-Barr Virus infection (but again, that covers 90 percent of the population), inadequate glutathione production… but an incredible number of these hypothesis are chicken-and-egg debates. Even less understood is how it strikes small children with “multisystem inflammatory syndrome.” Nor do we have any idea if the so-called “milder” Omicron (or the variants that will surely follow because wealthy countries have hoarded vaccines) will produce the same percent of Long Haulers as previous variants. Moreover, a lot of Long Haulers had an illusory recuperation from the acute phase of the virus, but were then were sucker punched with fatigue weeks later. It could take months to understand the long tail of the Omicron surge.

Thankfully Omicron rates seem to be falling (or people may just be testing at home and not reporting their cases). Even so, the lifting of mask mandates in mid-February 2022 seems insanely premature and based on social fatigue not science. We know from socio-cultural studies of risk that human perceptions of hazard are subjective, socially-inflected, and iterative (Auyero and Swistun 2009; Wright 1990)—meaning that peoples’ perception of risk shapes subsequent behavior and therefore alters their encounters with risk (Kellow 1999). Many studies show that repeated decision-making becomes a chronic stressor that eventually triggers paradoxical lapses in self-control, even reckless or arbitrary choices (Baumeister, Heatherton, and Tice 1994). Judges, for instance, are more likely to deny parole in the afternoon. When tired, one is more likely to make uni-dimensional decisions (e.g. selecting consumer items based on cost, not quality), heedless purchases (ergo, the location of “impulse” items at the check-out counter), or buy the junk food strategically placed at grocery checkouts. Car salesmen know full well how to break down a customer’s will power by reviewing a long list of options before a deal’s conclusion. I recognize that school boards are exhausted, but now is not the time to let down our guard.

Corporate collusions

Should you find yourself tempted to join the return to “normality,” please remember my vulnerable canary song and also consider who stands to profit from mass debility. In this blog (and the original article), I heretofore shared more about my health than my southern upbringing taught me is polite. Yet, as Clara Han (2018) argued, everyday stories at the ‘scale of the human body’ are needed to mobilize the full conceptual power of precarity from its critique of late capitalism into ideas of how we might collectively come together to face the overlapping environmental crises, economic crashes, and infectious pandemics—or what Singer and Clair (2003) aptly describe as “syndemics.” In fact, this week, U.N. Special Rapporteur David Boyd published a report that reminds us that premature death from pollution—from pesticides, plastics, electronic waste, and the like—far outpaces Covid mortality. In terms of pollution and pandemic morbidity, there may be a relation.

Allow me one last coda to this circuitous canary cantata.

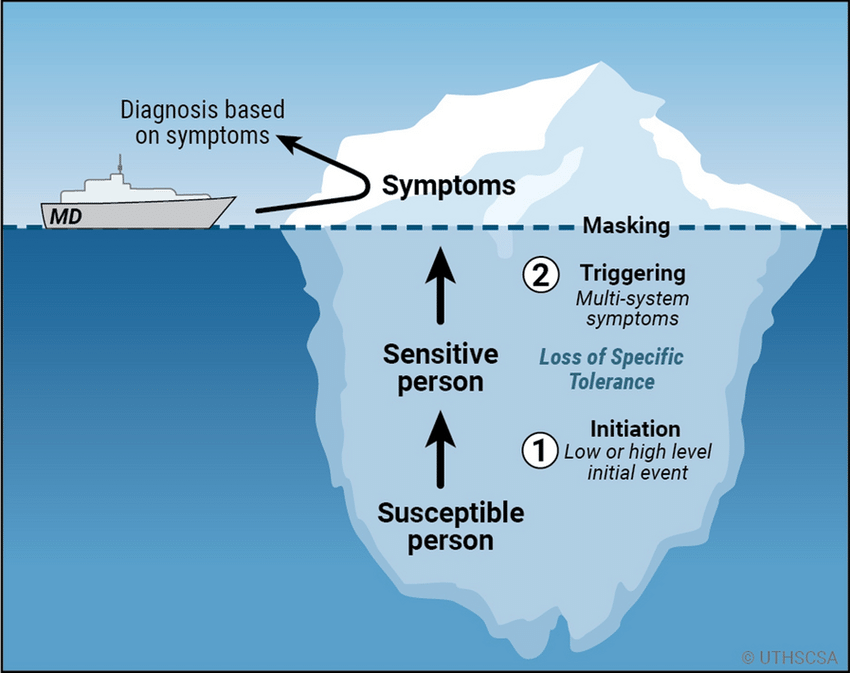

After twenty months of crushing fatigue and the emotional whiplash of repeated relapses, I seem to have cured most of my symptoms with alternative therapies suggested by other patients. I am back on solid ground and can walk a mile again. I wonder why I got better but others have not. I suspect one factor may be that I was already living a rigorously non-toxic life and eating an anti-inflammatory diet after surviving cancer at a young age. Through trial and error and a heightened sense of smell, I learned to avoid toxic triggers, especially synthetic fragrances. I developed a large bag of tricks to cope with mischievous mast cells and fragrance-induced dysautonomia. People with chemical intolerance (also known as “multiple chemical sensitivity”) suffer a smorgasbord of symptoms (brain fog, rashes, food intolerances, headaches, neuromuscular tension, problems with temperature control) caused by protracted hyper-arousal of the limbic system. The “fight or flight” response can save your life when you are fleeing a predator, but when it continues 24/7, it becomes disabling.

Many of my Long Covid comrades still trapped in their bedrooms. Fatigued and unable to go anywhere, they never escape their home environment. My hunch that after the multi-system assault of this wicked coronavirus, many long haulers have become sensitized to products in their own home they previously tolerated (carpet, cleaning chemicals, new furniture, melamine furniture, pest control and more). Are everyday chemical exposures exacerbating Long Covid inflammation? How would we ever know? Most people are enveloped in synthetically scented clouds 24/7, so they have no idea how much better they would feel without using these toxic products.

Long before facial coverings entered everyday parlance, Dr. Claudia Miller describes this quandary as “masking.”

This also begs a syndemic question: are the harsh chemicals used in the performative chemical disinfection of surfaces (for a virus we now know spreads by aerosols) leaving us more prone to and/or less able to recover from infection? Although buried in the avalanche of bad news, scientists are concerned that PFAS (per/polyfluoroalkyl substances that never break down) have the potential to disarm our vaccinations. These “forever chemicals” are found in everything from “hygienic” take-out food containers to anti-fogging sprays for eyeglasses worn with masks. It’s even in dental floss.

Johnson & Johnson (one of many companies whose toxic crimes are illustratively described in the longer article) brags that its brand of dental floss is PFAS-free. Lest J&J recreate its public image as a benevolent vaccine-maker (for which it received a $1 billion contract from the Trump administration), the public recently learned that this corporation quietly halted production of hundreds of millions of their single-shot vaccines (desperately needed in impoverished countries without refrigeration infrastructure for delivering the mRNA vaccines) in order to make a more profitable vaccine for a different virus (R.S.V.) for a clinical trial with Baby Boomers in wealthy countries.

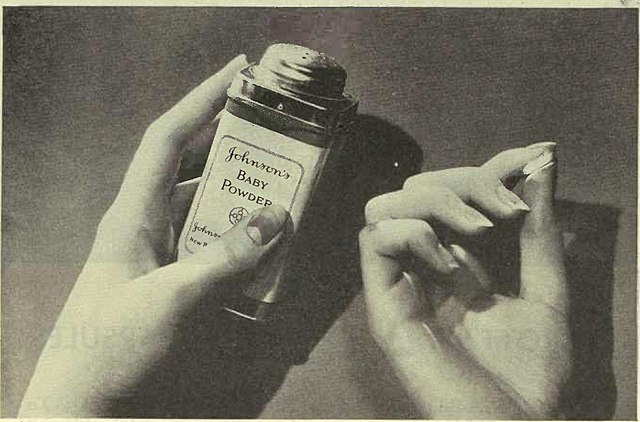

And in the few months since my Environment and Society article went to press, the J&J scandals continue accumulating. Parents reported that “extra sensitive” J&J baby wipes were causing mysterious burns. This past summer, the FDA discovered that J&J’s “natural” Neutrogena and Aveeno sunscreens contain disturbing amounts of benzene. A J&J subsidiary is also trying to declare bankruptcy to avoid class-action lawsuits for selling baby talc with asbestos for decades. [FIGURE 16][MOU2] The National Council of Negro Women is among those plaintiffs because J&J disproportionately marketed this ovarian- and mesothelioma-causing product to African American women. J&J and its asbestos supplier, Rio Tinto Minerals (a subsidiary of an infamous mining conglomerate responsible for destroying Indigenous homelands around the world) apparently hired scientific ghostwriters to downplay the evidence being weighed by the FDA. Oh, and Covid long haulers whose hair is falling out by the fistful should probably avoid J&J’s “thick & full” biotin + collagen shampoo because their OGX line apparently leaches formaldehyde when mixed with water.

Riffing off a sign I always carry to protests outside Monsanto’s facility in my hometown: I’ll believe a corporation is a person, and trust it as such, when Johnson & Johnson, like me, gets cancer, chemical intolerance, and then Long Covid.

Notes

[1] As background for those who might not have read this book in PoliSci 101, John Rawls (1971) proposed a provocative theory of equality based on a hypothetical birth lottery or what he called “a veil of ignorance.” Were people blind to what privileges in life they might be assigned, he argued they would always opt for equality in forming a social contract.

References

Achebe, Chinua. 1959. Things Fall Apart. New York: McDowell.

Auyero, Javier, and Débora Alejandra Swistun. 2009. Flammable: Environmental Suffering in an Argentine Shantytown. New York: Oxford University Press.

Baumeister, Roy F., Todd F. Heatherton, and Dianne M. Tice. 1994. Losing Control: How and Why People Fail at Self-Regulation. London: Academic Press.

Berman, Marshall. 1988. All That is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. New York: Penguin Books.

Bodley, John H. 1990. Victims of Progress. 3rd ed. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Callard, Felicity, and Elisa Perego. 2021. “How and Why Patients Made Long Covid.” Social Science & Medicine 268 (113426): 1-13.

Flynn, James, Paul Slovic, and C. K. Mertz. 1994. “Gender, Race, and Perception of Environmental Health Risks.” Risk Analysis 14 (6): 1101-1108.

Graeber, David. 2015. The Utopia of Tules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. New York: Melville House.

Han, Clara. 2018. “Precarity, Precariousness, and Vulnerability.” Annual Review of Anthropology 47: 331-43.

Kellow, Aysley. 1999. International Toxic Risk Management: Ideals, Interests and Implementation. New York: Cambridge Univeristy Press.

Miller, Gary W. 2013. The Exposome: A Primer. Oxford, UK: Academic Press, Elsevier.

Mohawk, John C. 2000. Utopian Legacies: A History of Conquest and Oppression in the Western World. Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Singer, Merill, and Scott Clair. 2003. “Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio‐social Context.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 17 (4): 423-441.

Starr, Chauncey. 1969. “Social Benefit Versus Technological Risk.” Science 236 (4799): 280-5.

Wright, Angus. 1990. The Death of Ramón González: The Modern Agricultural Dilemma. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Yong, Ed. 2021. “Long-Haulers are Fighting for their Future.” The Atlantic Monthly, September 1. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/09/covid-19-long-haulers-pandemic-future/619941/

Images

Karl Marx quote, Ivermectin, Longhaulers, J&J baby powder: Wikimedia, Public domain.

Things Fall Apart: Achebe, Chinua. 1959. New York: McDowell.

Cancer Blue: Aaron Tukey, 2008.

Bernie the Canary: Photo by author.

Fatigue: https://www.someecards.com/

Canary resuscitator: Science Museum Group.

Medical gaslighting: Spoonie Sanctuary

Endgame: Jinal Bhatt 2020

Denial: Think Before You Stink

Doctor dismissal: Trisha Greenhalgh

Masking: Fragrance Free Respect

Phenomenology of TILT: University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Disinfection: Bahareh Asadi, SNN.

Monsanto protest: Photo by author.

Liza Grandia, PhD, is Associate Professor of Native American Studies at the University of California-Davis. Beyond her work and activist research as an ally to Maya movements, she moonlights as Professor Canary to raise awareness about the risks of toxics exposure in everyday life.

See Dr. Grandia’s article “Canary Science in the Mineshaft of the Anthropocene” in the 2021 issue of Environment and Society: Advances in Research, Pollution and Toxicity: Cultivating Ecological Practices for Troubled Times.