Rains, rivers, tides, wells—waters, in their multifarious forms, have long shaped social worlds in and across Asia, as indeed in other parts of the globe. As the recent scholarship on its privatization, commodification, and trade, reminds us, water is a vital resource for human life. But it also exceeds such functions. Water mediates, reveals, nurtures, and obstructs social processes, as a site of mobility and immobility, cultural relationships and meanings, as well as political contestation and negotiations.

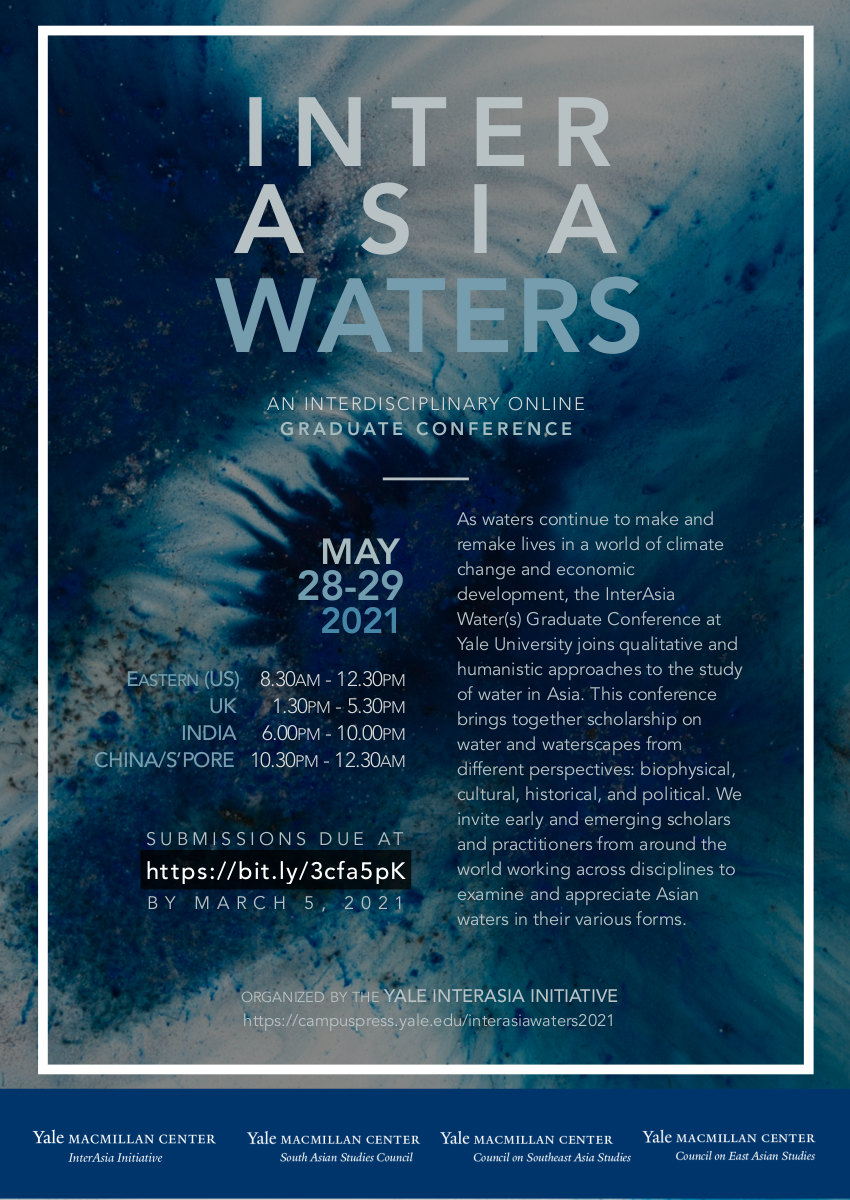

The InterAsia Water(s) Graduate Conference at Yale University, which took place on May 28 and 29, 2021, sought to shed light on such dynamism around this substance by taking an interdisciplinary and interAsian approach to the study of water. Over the course of two days, this international online conference featured a dozen presentations by graduate students from across the world, along with a keynote address by Professor Amita Bavisakar from Ashoka University.

To explore the multiplicity of the life of water across this vast and vibrant region, the conference was predicated upon two “inter-s”: interdisciplinarity and interAsia. As a rough indicator, we received dozens of abstracts from graduate researchers based in institutions in North America, South, East, and Southeast Asia, Europe, and Africa, and were fortunate to have presenters self-identified with disciplines such as Anthropology, Art History, Development Studies, Environmental Studies, Geography, History, Social Work, and Urban Studies. Perhaps it is something about water, that quintessential life substance, that affords and demands such a range of studies.

Further, the conference’s interAsia concept, which also guides the broader initiative at Yale, foregrounds the movements, histories, dynamics, and other processes that dis/connect these geographies. Building on the critiques of area studies grounded on the Cold War-era division of the world, the conference, like the Initiative, hoped to push “inquiries beyond nation-states, land-based demarcations, imperial zones, and cultural boundaries.” To this end, our panels deliberately juxtaposed studies that focus on seemingly disparate geographies through this fluid entity: Istanbul, Mumbai, and Sapporo, for example, and across diverse time periods from the seventeenth century to the contemporary. At the same time, such an interAsian focus challenges us to not only look beyond regional boundaries, but also take seriously the historical, linguistic, and cultural specificities that emerge precisely through such connectivities and disjunctures across time and space. In this regard, as a fluid yet material entity that preoccupies yet often defies human engagement, water offers a unique lens through which to understand “Asia” anew.

What emerged from these two “inter-s” is the multiple tensions that have animated and shaped human engagements with water in the interAsian regions. Our papers were thematically organized into four panels, each focusing on resistance, institution, planning, and meaning. Yet, following water led us to rethink these thematic rubrics themselves and pose a number of questions about the assumptions and conditions that enable these concepts.

The papers in the first panel, entitled “Fluid Frictions,” collectively underscored how regimes of power mobilize water as a site of control, whether through dam construction in Cambodia, technocratic monsoon management in Assam, or the immobilized labor conditions of hyper-mobile containership seafarers in Hong Kong and the United States. As another panel, “Institutions and their Discontents,” examined, these large-scale projects are often carried out by institutions that profess a moral pursuit of improving water access, spatial mobility, and economic productivity, in contexts both authoritarian and democratic, colonial and postcolonial. But these infrastructural projects, as highlighted in another panel, “Producing Urban Spaces,” can result in social and environmental disasters, revealing the ultimate impossibility of the technocratic dream of total control. They also inspire various alternative practices around water access and conservation from various levels, with the Ottoman state building water fountains with an emphasis on beauty, or citizen scientists in contemporary peri-urban India adopting quantitative data to counter urbanization.

If water and its various human uses thus implicate and move myriad actors, we might ask: How do we attend to the intermediary layers of power relations without glossing over hierarchies? How do we come to terms with the homogenizing impulse and the multiplying effect of modernist water infrastructure projects that create conditions for greater economic activity, social mobility, political control, and inequality at the same time? The conference highlighted the resonance of these double edges surrounding water across the different times and spaces represented in the diverse presentations.

These tenuous hydrological and social circumstances also raise questions about how communities reckon with their shifting relations with water. This concern guided the panel entitled, “Grounding Meaning,” which explored localized forms of meaning-making practices. Changing waters precipitate various attempts to make sense of them, as in the “game of blame” surrounding flooding in Jakarta. They also animate a range of desperate and aspirational action, as we see with farmers in Central India who drill tube-wells to access groundwater. As scholars try to make sense of the potency, fragility, and multiplicity of changing waterscapes, we might begin by inquiring into how our historical and ethnographic interlocutors themselves grapple with and act upon them.

In fact, the conference closed by reflecting explicitly upon this issue of historical resonance and reflexivity. That is, how might we make sense of the historical recurrence of the charisma and failure of high-modernist management, of neglect and reclaiming of indigenous knowledges, or of rupture and remaking of cultural meanings, around water? How do the insights and lessons from other times and places get forgotten, and how might they be engaged otherwise? As our keynote speaker Professor Amita Baviskar explored in her talk, considering the place of agency, of both humans and water itself, might offer us a good place to start.

Perhaps in the spirit of the fluidity of its theme, the InterAsia Water(s) Conference has given us more questions than answers. But it certainly became a platform for scholars, practitioners, enthusiasts and so on, to make and strengthen interdisciplinary and inter-regional friendships. These ties, we hope, will be the seeds for future conversations on this fruitful topic as the gift of rain nurtures us.

Notes and acknowledgements

The InterAsia Water(s) Graduate Conference was co-sponsored by the Yale InterAsia Initiative and the Councils on South Asia Studies, Southeast Asian Studies, and East Asian Studies at the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale University. The authors are grateful to the interdisciplinary team of graduate students who organized the conference with us: Chandana Anusha, Shalini Iyengar, Vanessa Koh, Al Lim, and Kelvin Ng. We also express our sincere gratitude to our faculty advisers, Professors Sunil Amrith, Erik Harms, Helen Siu, and Kalyanakrishnan Sivaramakrishnan, along with our keynote speaker, Professor Amita Baviskar. Our reflections here are also deeply indebted to the conference presenters and attendees, who generously shared their work and insights with us. A special thanks goes out to Dr. Yukiko Tonoike, Associate Research Scientist and Coordinator for the Yale InterAsia Initiative, whose hard work behind the scenes made the conference possible.

Lav Kanoi is a doctoral candidate in the combined Department of Anthropology and Yale School of the Environment joint PhD program. His dissertation project is on urban waterscapes in India and draws on literature and methods across the social sciences, the environmental humanities, and the natural sciences.

Shoko Yamada is a doctoral student in the combined program in the Department of Anthropology and the School of the Environment at Yale University.