The 1949 Fisheries Law in Japan underwent a historic revision in 2018, which went into effect in December 2020. The revision included the further application of science-based resource assessment, the introduction of the Individual Quota (IT) system, the expansion of the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) to more commercially targeted species, and the loosening of the entry restrictions to open fisheries to private companies. While the inclusion of scientific knowledge and approaches could deepen our understanding of oceans and marine species in the Anthropocene, most coastal fishing communities in Japan, whose fishing operation is local and cooperative-based, could find this revision a threat to their communal livelihoods due to its emphasis on rationalized single species-oriented approach to management, rather than a relational multi-species approach for their community wellbeing. This short essay aims to supplement and contextualize my recent article in Environment and Society (Hamada 2020) with the current state of Pacific herring fishery in Japan.

Japan’s domestic herring fishery was one of the largest fisheries in its national history and had its flourishing moment in the late nineteenth century, with the peak annual yield of 970,000 tonnes in 1897. However, the impact of overfishing and coastal and oceanic environmental changes led to collapse of the fishery for over a half century. Herring stocks around Japan ceased to return to shorelines for spawning beginning in the 1950s and became “commercially extinct” by the 1970s (Hamada 2014).

My recent article in Environment and Society discusses the development of Japan’s herring stock enhancement program through the perspectives of multispecies ethnography (Hamada 2020). Stock enhancement research and operation for commercially-targeted species has been in development since the late 1970s, in the face of coastal industrialization and subsequent environmental transformation, as well as geopolitical negotiations such as the international establishment of EEZs. In western Hokkaido, the herring stock enhancement project expanded in the late 1990s to early 2000s, involving national and regional fisheries scientists and technicians, local fishing cooperatives and fishers, and regional herring stocks.

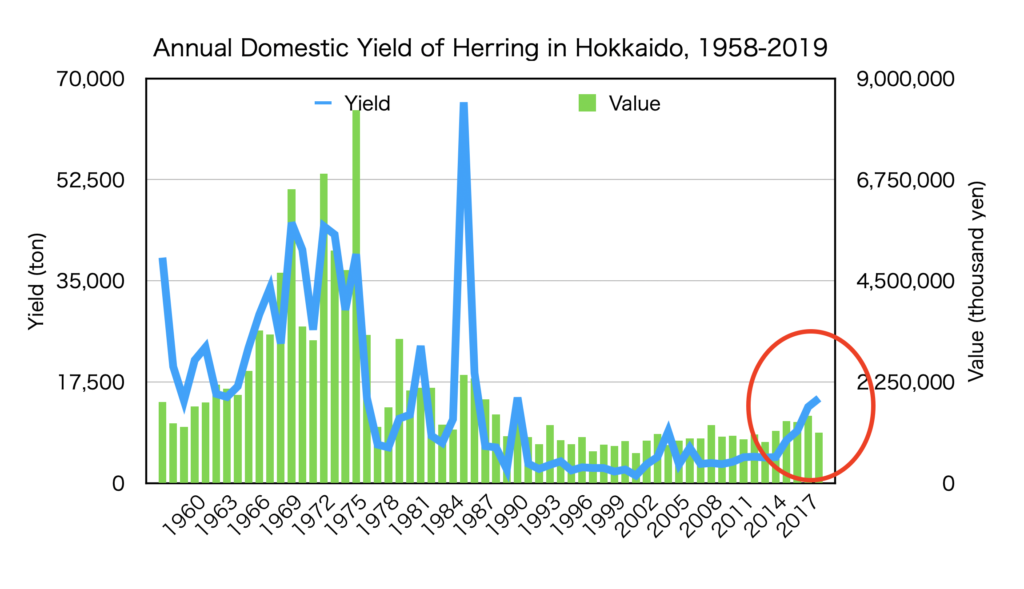

In recent years, the annual yields of herring are increasing. Public and business media report this increase as the herring ‘revival’, and connect it to hatchery enhancement efforts. In November 2020 the national fisheries agency assessed the current status of the herring biomass in western Hokkaido as ‘high level’, according to their scientific formula. They set an average annual yield in the last two decades (from 1995 to 2014) as the deviation value of 100. If an annual yield of a given year is valued over 140, the condition of herring resource is assessed as high level, as the resource is considered to be increasing based on the annual yields of the last five years. Considering that 53% of domestic fishery species are now assessed at a low level status, the recent increase of annual catches of herring is a rare good news story for the domestic fishing industry, and validates decades of stock enhancement projects as productive and meaningful intervention in nature.

However, when we examine Japan’s domestic herring fishery history over a longer period of time, it is questionable whether this recent increase is the recovery of once-depleted herring stocks, or a product of the Shifting Baseline Syndrome (Pauly 1995). Considering the historic number of annual yields over the past 150 years, the herring’s “high level” status seems to be both a scientifically and socially constructed factish (Latour 2010) image of abundance.

Resource assessment is a practice and result of relationships among multispecies actors. However, the contribution of stock enhancement science and technology in making coastal fisheries and ocean resilience becomes factish within the modernist work of purification and the circulation of selected information (Latour 2010). The current single-species approach of Japanese resource assessment deconstructs hybrid seascapes and reconfigures them by distinguishable species and fishing areas, in the spatial and temporal perimeters that scientists determine with their objectified yet potentially fetishized dataset. Overestimation of hatchery-operation could blackbox the objectivity and complexity of coastal resource and fishery management.

When we look at the current human-herring relationships in a broader perspective, changing foodways and gift practices in Japan continue to impact the market value of domestic and international herring and herring egg. Domestic consumption of kazunoko (herring roe) continues to decline, and 7 of 45 companies specializing in kazunoko processing in Hokkaido went out of business last year, most of which are small-scale local businesses.

On the other side of the North Pacific, the COVID19 pandemic prevented seasonal workers from traveling to Alaska, a labor shortage further limited operations of the herring fishery and seafood businesses , exacerbating the growing issue of of economically unsustainable low pricing of kazunoko in the international trade market.. The decision not to open the Alaskan herring fisheries and herring egg processing plants for lack of price also meansa dramatic decrease of herring product imports to Japan. That could certainly make the business of Japanese small-scale herring processors difficult in the coming years, as they depend heavily on imported fish and eggs from Alaska and British Columbia. Local processors began bidding and buying locally-caught herring, and boost the fish and egg marketing efforts that emphasized ‘the domestic’ over imports. However, the quality of herring fish and egg differs from region to region, even if it is under the same species category of Clupea pallasii, and therefore the “revival” of regional herring stocks around Japan does not necessarily meet all the country’s economic and culinary needs. Furthermore, the market price of domestic herring drops readily as the supply of domestic herring increases, given that herring is not TAC-regulated. So far, the revised Fisheries Law and factish recovery of domestic herring fishery in Japan do not seem to offer the solution that would make a sustainable, rich future for human-herring relationships to rival the herring heydays of the past in the western North Pacific.

References

Hamada, Shingo. 2014. Fishers, Scientists, and Techno-Herring: An Actor-Network Theory Analysis of Stock Enhancement Program in Japan. Ph.D. Dissertation. Department of Anthropology. Indiana University

Hamada, Shingo. 2020. Decoupling Seascapes: An Anthropology of Marine Stock Enhancement Science in Japan. Environment and Society. 11(1): 27-43 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2020.110103

Latour, Bruno. 2010. On the Modern Cult of the Factish Gods. Durham: Duke University Press

Pauly, Daniel. 1995. Anecdotes and the Shifting Baseline Syndrome of Fisheries. Trends in Ecology & Evolution (Amsterdam) 10(10):430.

Shingo Hamada is Associate Professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Osaka Shoin Women’s University, and Research Associate in the Department of Anthropology at Indiana University Bloomington. His research revolves around the environmental history and cultural politics of seafood in coastal communities, with a special focus on fermented seafoods and commoners’ fish such as herring and mackerel. Recent publications include “Gone with the Herring: Ainu Geographic Names and a Multiethnic History of Coastal Hokkaido” (Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 2015), and Seafood: Ocean to the Plate (coauthored with Richard Wilk, 2018), and several Japanese articles on merroir and coastal conservation. Email: shingohamada@gmail.com

See Dr. Hamada’s article, “Decoupling Seascapes: An Anthropology of Marine Stock Enhancement Science in Japan” in the 2020 “Oceans” issue of Environment and Society: Advances in Research.