The sun beats down from a muggy, overcast sky. It turns the small hummocks of a calm ocean to a hammered pewter sheet as far as the eye can see. I sit towards the front of the boat with the harpooner’s assistant squinting out at the waters of the Savu Sea. It’s the end of a long hunting day on the water and we will soon call it quits and head home to Lamalera empty-handed after following a pod of sperm whales moving eastwards. We’re the farthest I have been out this season, but as I look north to the island, we are still directly south of the small peninsula of Atadei, on Lembata’s southern coast. At this moment I realize the endurance of Lamalera’s previous generations of marine hunters: as far as we have come, we are nowhere near the edge of the community’s historical hunting range.

In the last issue of Environment and Society on oceans Florence wrote an article that analyzed recurring elements of the global debate about whaling, and how the debate both impacts and plays out within traditional and indigenous marine hunting communities. This article drew upon on-going research with marine hunters in Lamalera, Lembata (pictured above), Indonesia and compared it with ethnographic case studies from the Arctic and west coast of North America, including that of the Makah Tribe, in what is now Washington State in the US. That article examined the role of cetaceans –the order of whales, dolphins and porpoise– in the global environmental conservation movement, their specific charisma and mediatization, and the resulting types of cultural frames that have come to govern appropriate human-cetacean behavior. These frames, it argued, leave little to no room for legitimizing other ways of knowing cetaceans, as ancestors, as prey, as collaborators.

The evacuation of space experienced by traditional and indigenous marine hunting communities extends immediately beyond the realm of the global discourse, and the scope of that article, into the physical realm via contestations of marine tenure and border marking– an issue Sonja is examining in her PhD research on indigenous whaling policy across the Pacific. The physical re-framing, removal, and enclosure of marine spaces that hunting communities have experienced in the last century is an active focus of both of our respective projects, as well as other scholars of traditional and indigenous cetacean hunters. For this ARES blog post we return to a comparison of Lamalera and the Makah and an ongoing discussion about what the reduction of and exclusion from marine territory has meant for both groups.

Lamalera is a community of just under 2,000 people that sits on a rocky hillside behind a small cove on the southern coast of the island of Lembata, looking into the Savu Sea. For the past 500 years or more (Barnes and Barnes 1996) Lamalera’s residents have lived as marine hunters whose environment cosmology ties them in an unending feedback loop to the marine ecology of the Léfa, or sea, through a religious system blending elements of animism, ancestor worship, and later, Catholicism. At its core is the understanding that ancestors bring the whales, dolphins, and fish for Lamalerans to hunt and to catch, if they are found worthy.

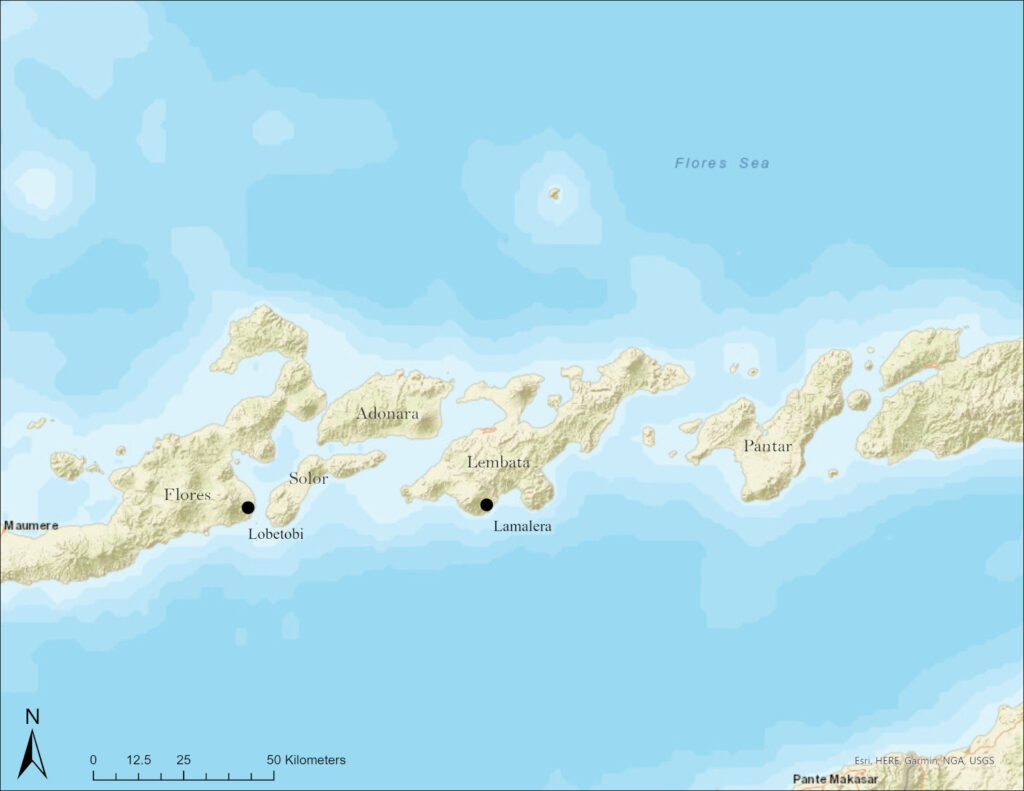

In the past decade Lamalera’s profile as the last traditional whalers of Indonesia has grown, and along with it a conflict about notoriety, marine conservation, and tradition. Commercial whaling is prohibited in Indonesia, as well as the capture of many other species that Lamalerans rely upon, such as rays and sharks. However, fisheries policies continue to leave grey areas for subsistence coastal fisheries, and there are legal routes to exception based on a group’s legal status as adat, or traditional or customary, that the community continues to consider. One of the larger elements of this conflict included an attempt to transition Lamalera from whale hunting to whale watching as part of an effort to bring the district into alignment with a larger provincial level plan to establish a conservation mandate for the Lesser Sunda Ecoregion, anchored with a series of networked marine protected areas (MPA). Attempts to move the community from hunting to a tourism-conservation model and to include Lembata’s southern coast in an island-wide MPA have been met with intense refusal from the community and its diaspora, culminating in a demonstration in the district capital. While it delayed planning in their local area, that effort has not shielded Lamalera or its hunters from the impacts of MPA implementation. This is because the historical range of Lamalera’s hunting grounds lay beyond their immediate coastal zone, extending from the waters off of the island of Solor and Flores to the west, to the southern coast of Pantar, the next island to the east. Access to these waters were secured through long-standing oral agreements with coastal village leadership where Lamalera’s boats hauled ashore (Barnes and Barnes 1996).

The fertile strait between Eastern Flores and the island of Solor used to be a significant end of season hunting ground for Lamalera, as well as for local hunting groups and travellers from Lamakera, Solor. A multigenerational agreement with the tuhan tanah, or lord of the land at Lobetobi, Flores allowed Lamalerans to camp on their shores in exchange for a portion of the catch (See Barnes and Barnes 1996 for description). Local populations focused on rays and small cetaceans but Lamalerans hunted for rays and sperm whale very successfully here, which they dried and brought home (ibid). Trips to the southern coast of Pantar were less frequent and more arduous than to Lobetobi, due to current and tidal patterns between the islands, and were made only to a specific area called Duli, where Lamalerans had an agreement with the community’s leaders. Trips to Pantar were made at the end of season after trips to Lobetobi, mainly for two species of ray and would last about a month (ibid).

Today, Solor, Lembata, and Pantar have all established MPAs. The waters off Pantar now sit within the Pantar Strait MPA, which was first established in 2006 and now encompasses the entire Alor Archipelago. This MPA specifically includes the conservation of cetacean and ray species that migrate through the nutrient-dense deep Strait between the islands of Pantar and Alor as part of its mandate. Trips to Pantar’s southern coast had become less frequent over the years as crewing boats for longer voyages has become difficult (see Durney, forthcoming). However, the establishment of the MPA meant all trips and, crucially, the possibilities for future trips came to an end. To the west, the strait between Flores and Solor now also sits within an MPA. District-level conservation efforts beginning in the 1990s started with enforcing bans of endangered species policies focusing specifically on manta ray. Stories have circulated in Lamalera through extended kin networks and social media about men who have caught rays being arrested and facing fines and jail time. Lembata also began the process of establishing an island-wide district level MPA, which was formally designated in 2012. The waters within the MPA as identified in planning maps wrap around the island but exclude a small section of the central southern coast where Lamalera is located, as a result of the community’s demonstration efforts. In 2014, laws governing maritime jurisdiction retracted governance of coastal zones from the district to the provincial level across Indonesia, but redistricting announced in 2019 will maintain largely the same MPA boundaries for these areas.

Combined, these changes have meant that Lamalera’s historical marine access has now been reduced to a very small fraction of what it once was. The sense of loss, disconnection, and hemming in that has resulted in Lamalera is significant. Perhaps most importantly it contributes to a pervasive feeling that hunters and residents report of being pressured on all sides, from fisheries policies, new economic burdens and outmigration, and, in this very real sense, reduced access. Trips to Pantar stopped outright, and the previous trading and cultural bonds connecting Lamalera with the island faded. Younger hunters have never been to Pantar, and would not attempt it, for fear of arrest by marine police. Solor remains much more closely tied to Lamalera’s habitus because of ongoing kinship connections, the fact that the islands remain in the same district, and that the island is located en route to both the district’s former and current capitals. But this habitus has a large hole, in that it no longer extends to hunting. This loss has material effects (decreased catch and a shorter average hunting season) but also specific social effects. Inter-community bonds maintained through catch sharing fade away, along with the deskilling of hunters who no longer know these waters. More intangibly, but no less significantly, a sense of regional identity and a shared sense of subsistence and connection to the marine ecosystem has been lost.

The Makah[i] are a people indigenous to the Northwesternmost point of the United States, the area around Neah Bay and waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. They share the strait with their linguistic and cultural relatives the Nuu-chah-Nulth and the Ditidaht peoples of Vancouver Islands, across the US-Canadian border. For thousands of years, the Makah have secured a livelihood from coastal waters of the North Pacific and the Salish Sea by fishing, sealing and whaling. While commercial fishing remains one of the mainstays of their economy today, the Makah halted their sealing and whaling activities in the 1920s due to global stock collapses and stricter hunting regulations (The Makah Cultural and Research Center 2021; Coté 2010; Collins 1996). Throughout the 20th century the Makah have faced multiple challenges to their right to fish and hunt in their customary waters, despite guaranteed treaty protections.

Historian Joshua L. Reid puts forth that Northwestern peoples have always asserted their claims over the tribally contested waters of the strait and the Pacific coast through activities such as fishing, sealing and whaling. Reid explains that historically both the Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth observed complex systems of ownership rights, which extended to include intangible objects in addition to propertied spaces, such as hunting or fishing grounds. Tenure rights were claimed by using the space and its resources, and tribal borders on the water were reproduced through conflict with rival chiefs. Thus, tenure was claimed and maintained through labour and livelihood. In short “by mixing their labor with the ocean through customary marine practices, Makahs transformed the sea into their country” (Reid 2015:143). He further points out that proprietary rights would also cover migratory prey, particularly whales, which were the allotment of the chiefs, who in turn reinforced their ownership of the whales and whaling grounds by sharing the catch with their own and neighboring communities. The Treaty of Neah Bay signed between the Makah and the colonial US government in 1855 largely dispossessed the tribe of their land. However, due to the prevailing political strength of the Makah chiefs in the region, the treaty included an uncommon admission of their marine tenure. Specifically, the treaty preserves the “right of taking fish and of whaling or sealing at usual and accustomed grounds and stations” (Treaty of Neah Bay 1855). However, conflicting ideas about what constitutes marine tenure have blocked Makah efforts to retain their rights.

According to Reid, one of the main sources of fishing and hunting disputes has been the common settler conceptualization of marine resources as open-access commons, whereas the Makah believed that the treaty protected their tenure over their customary waters and their proprietary right to the resource within them. In the early 20th century, the Makah had to give up both sealing and whaling due to the exhaustion of the animal populations by commercial hunters in their waters, and by the 1950s halibut and other fish stocks in the area were at a critical point. Throughout the century, state regulations aiming to reduce access and “prohibit tribal members from exercising their right to fish” (Coté 2010:117) challenged the Makah’s right to their customary waters despite legal protections. Eventually, the Makah and other Northwestern communities’ claims were validated by the 1974 decision in United States v. Washington, also known as the Boldt decision, which reaffirmed indigenous fishing rights. This secured the Makah the “…opportunity to take up to 50% of the harvestable number of fish…” in the waters covered by the treaty (United States vs. Washington 1974; Brown 1994; Harris 2008). For all that, only two years later the tribe lost access to some of the most important and productive halibut grounds on the Swiftsure and La Perouse Banks when the Canadian government declared an Exclusive Fishery Zone (EFZ) (Gray 1997). Halibut has formed one of the main sources of food and income for the Makah for thousands of years and the loss of access to the lucrative fishing grounds originally included in their ‘usual and accustomed grounds’ has been a key factor in significantly shrinking their catch in comparison to its historical size (Reid 2015).

Another source of mismatch over the drawing of the national and reservation borders has been what Reid describes as the Makah belief that “the sea was a medium of connections rather than a boundary of confinement” (Reid 2015:156). The marine tenure of the Makah, much like the essence of water, was in constant flux. The water functioned as a place not just of subsistence and livelihood, but also of meeting and communing with both neighboring kin and rival tribes, as well as passing on knowledge and forging and reinforcing social hierarchies through hunting and communication with nonhuman beings. On the water, borderland conflicts were regularly solved through both violence and kinship. The Treaty of Oregon was signed in 1846, just ten years prior to the Treaty of Neah Bay, ratifying the border of Canada and the US. The newly established border divided the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the middle and left the Northwestern peoples isolated within separate settler colonial states. Enforcement of national borders, EFZs and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) has disrupted kinship relations, the movement of people and knowledge, and inhibited trade and other economic activities. Records of traditional ecological knowledge and place-naming practices[ii] of the Makah demonstrate patterns of knowing and utilizing the fluctuating borderland waters beyond their reservation[iii] (Arima et al. 1991; Coté 2010). Negotiating cross-border movement on the water within the current parameters of border enforcement is a legally and bureaucratically complex process, which requires a disproportionate time and resource investment from indigenous communities.

Lastly, the drawing of borders does not only constitute an establishment of a physical barrier but is always accompanied by defining rules and regulations for maintenance and reinforcement within it. In the customary waters of the Makah, border management overlaps and intermingles with multiple state and federal mandates. They form a roadmap of legal borders, or frames, drawn by documents. One particular frame that has been used to box in Makah marine practice on several occasions is the emphasis placed on ‘subsistence’ clauses and the definition of indigenous practices and commercial activities as mutually exclusive. Regional trade, particularly of whale oil, was historically commonplace and central to Makah livelihoods and the maintenance of social relations within and beyond the community before colonial settlements and up until the late 19th century. Yet, both indigenous sealing and whaling have since been made conditional to a subsistence clause, diminishing the economic and cultural benefit of the hunts. The 1911 ban on pelagic sealing restricts the use of motorized boats, firearms and the sale of catch and quickly brought Makah sealing to a halt. In an attempt to bolster environmental protections through restriction of the Makah’s fishing rights, the Indian Claims Commission (ICC) and other agencies have claimed that the treaty rights cover only subsistence activities and that no legal protections exist to secure the Makah access to their primary source of livelihood and one of the largest industries in Neah Bay.

The tribe had also suspended their whaling activities in the 1920s to ease the pressure on whale populations on the brink of extinction due to industrial whaling by the US, UK and other whaling nations. In 1995, following the recovery of the gray whale population, the Makah, supported by the US federal government, submitted an application to the International Whaling Commission (IWC) for permission to resume their traditional whaling practice under the exception for Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW). After an initial rejection of the application, the IWC and the Makah settled on a mutually acceptable compromise of quota sharing with the Chukchi people of Russia, which resulted in the allocation of a quota of 20 gray whales for the Makah for a five year period [iv]. In the spring of 1999, after a 70-year long hiatus, the Makah hunted a whale. The rest of the allocated quota was left unused, however, as a 1998 lawsuit against the federal government over their approval of the hunt eventually delivered a verdict to suspend the Makah whale hunt, pending a new environmental study (Monder 2015).The ASW application process required the Makah to devalue the importance of trade for their whaling tradition, but even with IWC approval they have not been able to satisfy the cultural needs that served as the premise for their request. Currently, the Makah are still in the process of securing their treaty-protected right to whale [v].

The problems of commons and enclosure in conservation practice for local and traditional peoples have a long and well-documented history within environmental social sciences (See reviews by West et al 2006 and Dove 2006; See also Duffy, Brockington and Igoe 2008; Büscher et al 2014). The experiences of the Makah and Lamaleran communities shed light on the particularities of territorial shrinkage in traditional marine tenure contexts, where fluidity and fluctuation remain inarguable forces. Of course, case study comparison is imperfect, and it is important to note that both groups are grappling with oceanic loss from significantly different contexts. Lamalera is midstream in an effort to maintain marine access and to keep a traditional identity and livelihood system alive in a rapidly growing and changing post-colonial Indonesia. The Makah struggle is more heavily burdened by the process of reclaiming rights and reviving traditions, a process which must be sieved through the complex legal relationship that federally recognized tribes have within the United States. The comparison of the two remains fruitful though in showing how externally constituted marine borders (both national and internal in the form of marine parks and local jurisdictions) and the legal frameworks established for their enforcement have often proved uniquely unable to accommodate historical and traditional ways of claiming marine tenure and living with the ocean. The impact of these shortcomings are far-reaching and deeply felt by these communities and others that practice such ways of being in the world.

In the US, the tendency to “…commonly envisage American Indians as a quintessentially terrestrial people” (Bahar 2014:406) and the subsequent failure to understand indigenous marine tenure has had an all-encompassing impact on the lives and livelihoods of the Makah and other Northwest peoples. Scholars like Reid have worked to document and bring forward the multifaceted meanings and makings of this tenure. Ultimately, the nature of water, marine landscapes and the life that dwells in them is to be in flux. A border on the water does not reroute currents, halt the migration of salmon, stop the constant flow of nutrients or slow down tidal cycles. The Makah have claimed territory, status, and identity through knowing, naming and mapping the fluctuating maritime and coastal worlds around them, but the extent or cultural significance of their form of marine tenure is not adequately reflected in border and policy making at either the state or federal level. For Lamalerans, the ever-reducing access to historical hunting grounds has manifested in a fear that traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) about these grounds and how to access them cannot be maintained for future generations, and in a sense of isolation in their struggle to maintain a culture and livelihood system in an archipelago that was formerly filled with shared points of connection.

For both communities then, lack of access to specific marine spaces has meant far more than loss of tenure or catch, though that too is important. Lefebvre would remind us that places are mutually constituted with and through cultural practices (1974), and the shrinking of territory is paced by the shrinking of cultural worlds. For marine hunting communities the exclusion from access to territory and resources has represented a rupture of cultural continuity that is difficult to overstate. For example, how does one maintain a tradition of knowing and naming a seasonally relevant and area-specific marine phenomena (Arima et al 1991) without being able to witness or experience it? For the Makah, maintaining a cultural identity as hunters without the ability to do so has been an act of incredible perseverance. Many residents of Lamalera can envision future generations that may need to do the same.

Scholars of traditional and indigenous ecological knowledge systems have long argued that such systems rely on embodied, experiential practices tied to time and place (Berkes 1999, Kimerer 2013) and in a marine context place takes on a mutable meaning. For such practice-reliant and location-episodic ways of being or dwelling (Ingold 2005, Knudsen 2008), access to marine spaces is only the starting point. Further, borders are difficult to reconcile with environmental cosmologies and TEK systems that foreground highly mobile non-human actors, as is the case for both communities discussed here. To this end, for this year and next we are continuing to examine the intersection, and collision, of ways of knowing and claiming cetaceans and the marine spaces they pass through in the Pacific, as part of a larger European Research Council funded project called Whales of Power at the University of Oslo.

Notes

i. The Makah refer to themselves as qʷi·qʷi·diččaq (the people who live by the rocks and seagulls), the name Makah (the people who are generous with food) was given to them by others and has since been widely used in official context and media For more see: The Makah Cultural and Research Center, 2021; Reid, 2015; Coté, 2010; Erikson, 2002

ii. For more on indigenous place-naming, see Basso, Keith Wisdom Sits in Places, 1996, University of New Mexico Press

iii. Known places recorded in Arima et al. include locations such as Swiftsure Bank off the coast of Vancouver Island

iv. For more on the Makah case in the IWC, see https://iwc.int/makah-tribe

v. For more, see press statement by the Makah on their current negotiations with the state in collaboration with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), available online at https://makah.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Makah-Tribe-Press-Release-re-FR-notice.pdf ; for NOAA summary of their collaboration with the Makah, see https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/west-coast/makah-tribal-whale-hunt

vi. Both maps for this piece were created with help of Rachel Durney

References

Arima, E.Y. at al., 1991. Between Ports Alberni and Renfrew: Notes on West Coast Peoples. Canadian Museum of Civilization

Bahar, M.R., 2014. People of the Dawn, People of the Door: Indian Pirates and the Violent Theft of an Atlantic World. The Journal of American History, 101(2), pp.401-426.

Barnes, R.H. and Barnes, R.H., 1996. Sea hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and weavers of Lamalera. Oxford University Press

Berkes, F. 1999. Sacred Ecology. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management.Taylor and Francis, London.

Brockington, D., Duffy, R. and Igoe, J., 2008. Nature unbound: conservation, capitalism and the future of protected areas. Earthscan.

Brown, J.J., 1994. Treaty rights: Twenty years after the boldt decision. Wicazo Sa Review, pp.1-16.

Büscher, B., Dressler, W. and Fletcher, R., 2014. Nature Inc.: environmental conservation in the neoliberal age. University of Arizona Press.

Coté, Charlotte. 2010. The Spirits of Our Whaling Ancestors: Revitalizing Makah & Nuu-chah-nulth Traditions. University of Washington Press

Collins, C.C., 1996. Subsistence and survival: the Makah Indian reservation, 1855-1933. The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 87(4), pp.180-193.

Dove, M.R., 2006. Indigenous people and environmental politics. Annu. Rev. Anthropol., 35, pp.191-208.

Gray, D.H., 1997. Canada’s unresolved maritime boundaries. IBRU Boundary and Security Bulletin, 5(3), pp.61-70.

Harris, Douglas C.. 2008. “The Boldt Decision in Canada: Aboriginal Treaty Rights to Fish on the Pacific” ed. Harmon The Power Of Promises: Rethinking Indian Treaties In The Pacific Northwest, 128-153 University of Washington Press

Ingold, T., 2005. Epilogue: Towards a politics of dwelling. Conservation and Society, pp.501-508.

Kimmerer, R.W., 2013. Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

Knudsen, S., 2008. Ethical know-how and traditional ecological knowledge in small scale fisheries on the eastern Black Sea coast of Turkey. Human Ecology, 36(1), pp.29-41.

Lefebvre, Henri, and Donald Nicholson-Smith. 1991.The production of space. Blackwell: Oxford

Khoury, Monder., 2015. Whaling in Circles: The Makahs, the International Whaling Commission, and Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling. Hastings LJ, 67, p.293.

Reid, Joshua L., 2015. The Sea is My Country: The Maritime World of the Makahs. Yale University Press

Treaty of Neah Bay, 1855, Neah Bay, available online at https://goia.wa.gov/tribal-government/treaty-neah-bay-1855

West, P., Igoe, J. and Brockington, D., 2006. Parks and peoples: the social impact of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol., 35, 251-277.

Florence Durney is an environmental anthropologist and Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages at the University of Oslo focusing on traditional and small-scale coastal communities in Southeast Asia and their adaptations to a changing social and environmental context. She has published and been a contributor in both social science and applied venues, and has done research focused on Indonesia, Melanesia, the US-Mexico border, and California. Email: florence.durney@ikos.uio.no.

Sonja Åman is a Doctoral Researcher at the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages at the University of Oslo focusing on policy making and indigenous whaling in the Pacific. Email: s.i.aman@ikos.uio.no

See Dr. Durney’s article, “Appropriate Targets: Global Patterns in Interaction and Conflict Surrounding Cetacean Conservation and Traditional Marine Hunting Communities” in the 2020 “Oceans” issue of Environment and Society: Advances in Research.