In 2020, the world watched as climate, public health, economic, and racial justice crises converged. It has become increasingly evident that failures of collective and public policies around health and the environment have perpetuated individual suffering. If ever there was an opportunity for the collective to re-think business as usual… it is now. We are firmly situated in the Anthropocene: a time in which human activities are arguably driving our climate and changing environment. The ocean is not exempt from these human influences. Indeed, human energy demands and associated carbon emissions, unsustainable extraction of living and non-living marine resources, land-based activities, and natural processes are contributing to significant changes in marine and coastal environments. These changes include the persistence of plastic waste in most, if not all, ocean ecosystems and species, reduced oxygen and lower pH levels in coastal waters, unprecedented shifts in the range and distribution of marine species, and sustained elevated ocean temperatures over time and space, among others. These conditions exemplify what we are now calling the Anthropocene Ocean. The Anthropocene Ocean is also occurring amidst rapidly changing societies and associated limits to land-based industrial expansion; feeding an emerging narrative about the economic potential of the ocean and its resources (Campbell et al. 2016). Our rapidly changing ocean is also now perceived as the next frontier for growth and expansion of our global economic system.

Novel and changing conditions require novel and adaptive responses. As with the range of threats experienced in 2020, shifts in global ocean and economic conditions are disproportionately affecting vulnerable communities and individuals who intimately depend on ocean resources for their livelihoods. The current foundations of ocean governance emerged in the mid 20th century, at a time when nation states were the central players; competing to assert naval power by claiming sovereignty and jurisdiction over ocean spaces and resources. But change is upon us. In our paper we argue that the Anthropocene Ocean era is faced by the new challenge of linking development and sustainability to address intersecting problems like climate change and poverty. A single-focus approach on fisheries or pollution is no longer sufficient. Indeed, the task at hand requires a holistic approach that considers people, climate change, conservation, and the sustainable use and management of resources… no simple feat. The era of the Anthropocene Ocean is also characterized by a diversity of actors and policy approaches, often facilitated by technological innovation both in communication and information sharing, as well as in ocean observation and industrial capabilities. In practice, this era was cemented with the establishment of UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in particular SDG 14: Life Under Water; and supported by international programs such as the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, and a variety of national and regional-level efforts that have elevated our oceans front and center on the global development stage.

Without a doubt, this is a crucial time for the future of ocean governance, defined in our paper as the level and manner in which power and authority are exercised not only by governments but increasingly by non-governmental institutions such as industry and civil society. An evolving, and perhaps more mature, sustainable development agenda can provide a unique platform for this new ocean governance era around three key themes: the role of voluntary commitments towards global goals, the promise of the blue economy, and the role of integrated marine planning using technological innovations as tools for ocean governance. In our paper, we review the evolution of ocean governance and identify key challenges and opportunities for the future.

I’ll start with the challenges:

- Global Targets and Voluntary Commitments: Along with the growing recognition of the importance of sustainably managing the ocean, scholars have documented an increase in the number of voluntary commitments made (e.g. establishment of protected areas) and global targets (e.g. percentage of the ocean set aside for conservation) set by nations, philanthropic foundations, academia, NGOs, industry, and intergovernmental groups (Grorud Colvert et al. 2019). Yet, it is often difficult to hold sectors accountable to their commitments, and commitments are also difficult to assess and track.

- Spatial versus Functional Approaches to Ocean Governance: As recognized in the early days of ocean governance, there is a mismatch between natural processes (e.g. ecoregions), geopolitical jurisdictions and power (e.g. political boundaries), and single-sector approaches (e.g. fisheries). This mismatch, as a governance challenge, is only exacerbated by intersecting and cross-cutting threats such as climate change.

- Lack of Comprehensive and Meaningful Action and Practice for Equity Considerations: There is growing recognition of disproportionate burden experienced by vulnerable communities, in comparison to sectors, industries, and nations driving some of the most important changes to our climate and environment. Additionally, shifts to market-based solutions and emphasis on procedural efficiency as exemplified by management tools like marine spatial planning further raise questions of how to ensure equity and justice for the most vulnerable.

Growing interest in the ocean, however, also presents great opportunities that merit further exploration:

- We have a unique opportunity to redefine ocean narratives. Existing scholarship and governance frameworks can pave the way for a better ocean future. It is my hope that lessons from 2020 might further help us envision, design, and support a more equitable ocean governance. The global community is faced with addressing critical questions about how we deal with climate, public health, economic, and racial justice crises. The Anthropocene Ocean is now part of that future with calls to elevate equitable conservation and sustainability within the ocean economy.

- In order to act upon those new narratives, there is also an opportunity to support novel institutional arrangements. Global platforms for making ocean commitments can elevate the power and voices of diverse stakeholders and rights holders to secure place-based solutions. In other words, future governance can and should give power to those who need it, and support equitable transfer of technology and information.

- And lastly, there is no question that we are firmly in an era of data science. It is more important than ever that data science be inclusive in terms of who participates in the scientific process and who benefits from scientific outcomes. Ocean governance practitioners, scholars and decision-makers must draw from interdisciplinary science and technologies that are co-produced to address specific problems and all their complex human, natural, and technological dimensions.

I look forward to working collaboratively to capitalize on these opportunities, as I continue to develop my engaged scholarship in partnership with the incredible, compassionate and thoughtful scholars, colleagues, and friends from Oregon State University, the Nippon Foundation’s Ocean Nexus Program, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Coiba Research Station – AIP in Panama.

References

Campbell, Lisa M., Noella J. Gray, Luke Fairbanks, Jennifer J. Silver, Rebecca L. Gruby, Bradford

A. Dubik, and Xavier Basurto. 2016. “Global Oceans Governance: New and Emerging

Issues.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 41: 517–543. https://doi.org/10.1146/

Grorud-Colvert, Kirsten, Vanessa Constant, Jenna Sullivan-Stack, Katherine Dziedzic, Sara L. Hamilton, Zachary Randell, Heather Fulton-Bennett, et al. 2019. “High-Profi le International Commitments for Ocean Protection: Empty Promises or Meaningful Progress?” Marine Policy 105: 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.04.003

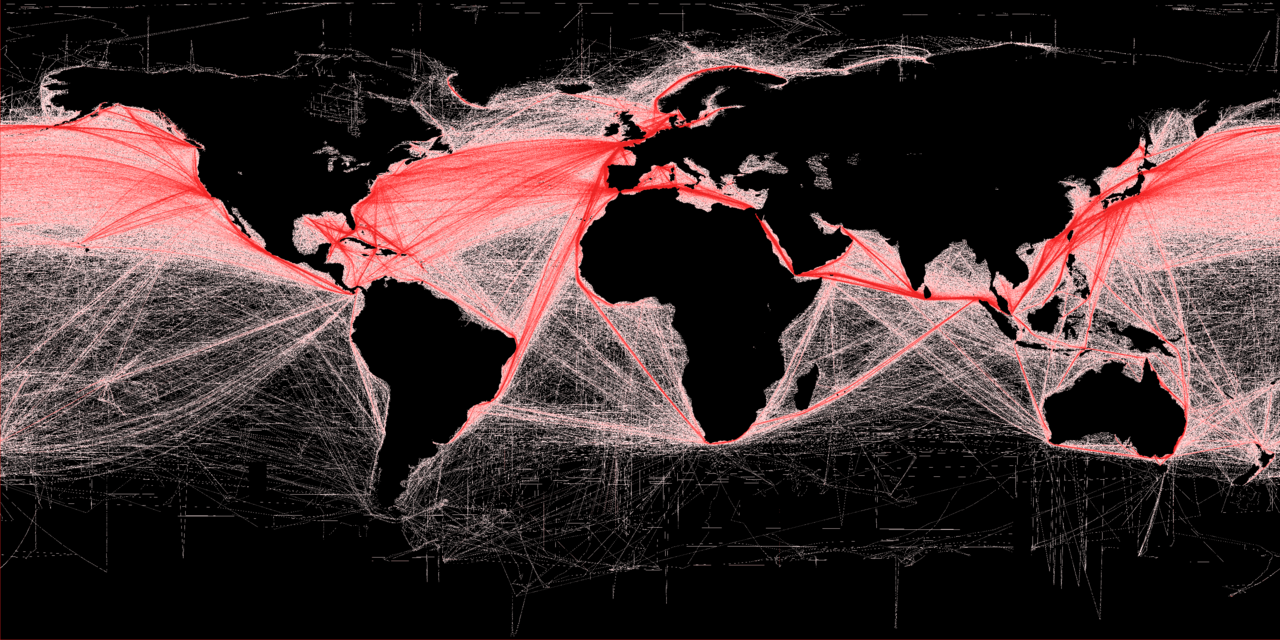

Shipping routes image: Shipping density (commercial). A Global Map of Human Impacts to Marine Ecosystems, showing relative density (in color) against a black background. Author: B.S. Halpern (T. Hengl; D. Groll) / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

Ana K. Spalding is Assistant Professor of Marine and Coastal Policy at Oregon State University, and Research Associate at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Coiba Scientific Station (COIBA-AIP) in Panama. She holds a PhD in Environmental Studies from the University of California, Santa Cruz; an MA in Marine Affairs and Policy from the University of Miami; and a BA in Economics from the University of Richmond. She has published widely on the links between people, the environment, development, policy, and property rights in Latin America. She also has more than 15 years of experience working in development and conservation in Panama. Email: ana.spalding@oregonstate.edu

See Dr. Spalding’s article (co-authored with Ricardo de Ycaza), “Navigating Shifting Regimes of Ocean Governance: From UNCLOS to Sustainable Development Goal 14” in the 2020 “Oceans” issue of Environment and Society: Advances in Research.