This post is presented in this week’s series recognizing Earth Day, Friday, April 22.

This Is Trauma

“This is trauma,” suggested one facilitator as the sun set over a planning meeting for the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe – Lowlander Center Resettlement held in January of this year. In a community space raised high above the banks of Bayou Pointe-Au-Chien, a handful of teenagers, adults, and elders from the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe had spent the last hour sharing their experiences of storms, flooding, displacement, disrupted community, and racism mediated by environmental crises and the official responses to them.

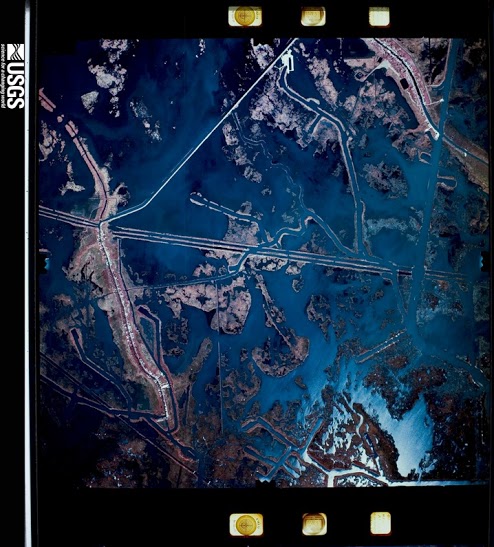

The Tribe has inhabited their small island in southeast Louisiana since the relocation programs of the Indian Removal Act era displaced its ancestors from Biloxi, Chitimacha, and Choctaw tribal lands. Members are now facing another displacement, as over 21,000 acres of the Tribe’s land has washed away in the past sixty years. Levee infrastructures prevent the Mississippi River from replenishing the delta with new sediment while an immense web of oil pipeline canals allows salt water to creep up the bayous, killing flora and intensifying coastal erosion. Sea level rise also contributes to the loss of land, which, as Monica Patrice Barra’s recent Engagement post discusses, occurs at more than a football field every hour.

The environmental hazards compound with distinct social and political challenges and experiences of environmental racism. A planned 72-mile floodwall called the Morganza to the Gulf Hurricane Protection Project cuts off Isle de Jean Charles and their traditional lands from the rest of Terrebonne Parish, further intensifying and materializing the Tribe’s exclusion and vulnerability. Their Island was initially included in the storm protection system but was removed from the protective area after a 2005 cost-benefit analysis that ignored local knowledge and social costs. Today, only 320 acres of land remain of the 22,000 that existed in 1955, forcing Chief Albert Naquin and his Tribal Council to make the difficult decision to move to higher ground.

The Tribe has worked toward resettlement for almost twenty years. In 2002, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) began planning their relocation but required 100 percent agreement to move from the community. Many people were reluctant to leave due to concerns that the government would lease out ancestral lands to oil companies, some of which had already taken land from individual families. When the vote finally occurred, the USACE’s lack of knowledge about the community makeup and intertribal politics led it to count nonmembers of the tribe in the vote. Another attempt in 2008 was foiled by racist NIMBYism and discrimination up the bayou—a problem that tribal members have faced consistently, especially since the desegregation of Terrebonne Parish schools in the 1960s. These repeated disappointments led the Tribe to partner with their long-time collaborators at the Lowlander Center to develop a resettlement plan that would employ best practices and put the Tribe in control of their own resettlement.

Resilience, Refugees, and Racism

This particular community meeting was held just weeks before the Tribe learned that their application and resettlement plan had won $48 million from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)’s National Disaster Resilience Competition (NDRC). The NDRC award has generated immense hope and excitement within and outside the Tribe. Since the award announcement, the Tribe has received an overwhelming amount of support and media attention.

As an anthropologist, I have focused on disaster media worlds (Ginsburg et al. 2002)—how the reproduction and circulation of representations of disaster constitute sites of social encounter—and how land loss mediates social relations and senses of place in ways that are extended through and complicated by audiovisual media. I have been following this heightened visibility, and some of the conversation surrounding coverage of the resettlement raises urgent questions of what resilience will mean in the context of community resettlement as a form of climate adaptation in the United States.

Journalists and bloggers have been quick to dub the tribe “America’s first climate refugees.” This moniker is misleading because there are a number of other indigenous communities planning resettlements due to coastal hazards associated with climate change. Community leaders have also resisted the term out of concern that it might conjure images of scattered and unorganized fleeing masses. The Tribe has been proactive, organizing within their community, building partnerships, conducting outreach, and guiding the resettlement planning process. Members have worked tirelessly to become leaders in the effort to adapt.

In fact, the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw – Lowlander Center partnership is so compelling because of its potential to apply and produce best practices for use elsewhere. The lessons learned will be increasingly valuable with 13.1 million US coastal residents expected to face climate displacement this century. Marion McFadden, deputy assistant secretary for grant programs at HUD, conveyed that their interest in the Tribe’s success lies in the learning potential for a government-sponsored, community-driven resettlement. Bren Hasse from Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority expressed similar sentiments about the potential to learn from their success. I worry, however, that the framing of the Tribe as refugees may unintentionally focus on the imminent need for housing while sidelining other critical dimensions of a successful community resettlement and teaching community.

The reduction of resettlement to housing for individual families is already evident in the online comments that associate the dollar amount in the grant with the number of families living on the island. Comments like, “$48 million … 27 families … that’s 1.75 million per family … get a pretty nice condo in Destin?” and “I am considering moving down there so I can get $420,000 to relocate,” and “$48,000,000 divided by 100 residents equals around $480,000 each; a pretty good relocation package. If the house in the picture is any indication of what they’re leaving, those 100 people have to think they’ve just won the lottery.” Such comments display a lack of understanding of the costs of building infrastructure, and of utilizing federal dollars wisely so as to ensure that expenditures made today do not have to be repeated in the future. Additionally, they deploy a notion of family as discrete social units, ignoring the Tribe’s social organization, kinship relations, and sense of community.

These comments reflect a larger racist narrative that discounts the Tribe’s set of practices and history as distinct from neighboring tribes, campers, Cajuns, and an array of other ethnic communities who also inhabit the region. Social distinction has enabled the Isle de Jean Charles Tribe to escape genocide in previous generations and continues to serve as a central tenant of their sovereignty. To frame the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Resettlement as a relocation of individual families renders their social structure invisible and asserts a colonizer’s paternalistic frame that disintegrates the Tribe’s collectivity and agency. The idea that resettlement is only about relocating families would exacerbate the effects of their displacement while resembling the same ideas that guided assimilation programs during previous colonial encounters.

Best Practices

Moreover, the tribe’s capacity to serve as a model community for resettlement would be completely undermined if the resettlement were focused on providing housing at the expense of the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw’s tribal coherence, ways of life, and capacity to grow and be resilient and self-sufficient. To do so would be in violation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and a number of other best practices established by anthropologists and resettlement experts over the past forty years. It would doom the resettlement to what Michael Cernea describes as social disarticulation. According to Cernea:

Forced displacement tears apart the existing social fabric. It disperses and fragments communities, dismantles patterns of social organization and interpersonal ties; kinship groups become scattered as well. Life sustaining informal networks of reciprocal help, local voluntary associations, and self-organized mutual service are disrupted. This is a net loss of valuable “social capital” that compounds the loss of natural, physical, and human capital. (2000: 30)

Resettled communities who experience disrupted networks of mutual aid, disintegrated community rituals, religious institutions, kinship structures, and sense of ethnic cohesion experience consistently worse outcomes. For example, Art Hansen (1992) observed that Angolans who resettled themselves alongside members of shared ethnic communities in Zambia had better outcomes than those displaced to camps with members of other ethnic groups (cited in Oliver-Smith 2005).

A similar dynamic threatened the Beles Valley resettlement in Ethiopia in the late 1980s, when new social and ethnic arrangements repeatedly undercut efforts to rejuvenate lifeway institutions[1] and informal associations (Abutte 2000). Social disarticulation can lead to new conflicts and the loss of connections to sacred spaces (Oliver-Smith 2005). These dynamics have doomed or seriously threatened community resettlements in India (Mahapatra and Mahapatra 2000), Belize (Palacio 1982), Peru (Oliver-Smith 2009), China (Rogers and Wang 2006), Mozambique (Witter and Satterfield 2014), New Orleans (Button 2009), and around the world. Kyle Whyte (2014), Julie Koppel Maldonado et al. (2013), and Robin Bronen (2015) have also demonstrated the need for resettlement policy to ensure community coherence throughout the resettlement process. This is why it is so essential that the Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement is not simply a family relocation program or a housing project despite the narratives that individuals who do not understand the project and racist Internet trolls may perpetuate.

Indigenous communities whose social systems are often rooted in place, and who have long experienced the legacies of forced relocation, are already experts on the social dimensions of resettlement. As Micha Rahder discussed in a recent Engagement blog post, drawing from Daniel Wildcat (2009)’s notion of indigenuity, there is expertise that emerges from “the long histories of knowing as doing, relation with place, and responding to environmental and colonial change.” The Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw’s community resettlement has already given enormous hope to tribal members and to neighboring tribes, but that hope relies on the survival of their community and their ways of life—an insight that seems to be missing from the media debates on the resettlement.

Hope for “Just Resilience”

Those present at the meeting in January were deeply aware of the indigenuity driving the resettlement this time around. It was evident in the heavy silence that followed the suggestion of trauma. To the agreement of the folks in the room, the facilitator responded, “With intergenerational trauma also comes intergenerational wisdom … so we have strength.” Media makers, online commenters, state representatives, and anthropologists must acknowledge the strength, wisdom, and experience that the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe have cultivated through generations of “living down the bayou” and adapting to social and environmental catastrophes that include colonialism, displacement, desegregation, racism, extraction, more displacement, storms, flooding, and more displacement.

The NDRC funds and other official resilience programs must draw from notions of resilience following the best practices developed by anthropologists and motivated by what Rev. Richard Krajeski at the Lowlander Center has repeatedly called just resilience—one that emphasizes ethical and moral best practices of resettlement and prioritizes solidarity with people-of-place, their places, ecological relationships, and subsistence-resilient ways of life. This philosophy of resilience emphasizes the need to sustain and support local social organization and tribal sovereignty. The Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement has great potential for success on these fronts and in terms of physical resilience. As a student committed to engaged anthropology, that gives me hope. I am also learning, however, that there is so much work to be done and that the Isle de Jean Charles Tribe and other coastal communities will be in a much better position to address the traumas of displacement if we actively resist versions of “resilience”—no matter how well intentioned—that may further disintegrate communities and destroy ways of life. Happy Earth Day, y’all!

Nathan Jessee is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at Temple University. Working alongside the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw and their resettlement team, Nathan uses participatory action research, media anthropology, and a decolonization framework to understand experiences of displacement and community resettlement necessitated by coastal land loss in southeast Louisiana. The dissertation work will be supported with funding from the Wenner-Gren Foundation.

Note

[1] Lifeway institutions include the everyday organization of food systems and informal care networks that may not fit the common use of term “cultural” institutions that often describe museums and community centers and may not be counted by those who do not understand lifeways but are nonetheless important for survival and become more so in the midst of community resettlement.

References

Abutte, Wolde-Selassie. 2000. “Social Re-Articulation after Resettlement: Observing the Beles Valley Scheme in Ethiopia.” Pp. 412–430 in Risks and Reconstruction: Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees, ed. Michael Cernea and Christopher McDowell. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Bronen, Robin. 2015. “Climate-Induced Community Relocations: Using Integrated Social-Ecological Assessments to Foster Adaptation and Resilience.” Ecology and Society 20, no. 3.

Button, Gregory. 2009. “Family Resemblances between Disasters and Development-Forced Displacement: Hurricane Katrina as a Comparative Case Study.” Pp. 255–274 in Development and Dispossession, ed. Anthony Oliver-Smith. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research.

Cernea, Michael M. 2000. “Risks, Safeguards, and Reconstruction: A Model for Population Displacement and Resettlement.” Pp. 11–15 in Risks and Reconstruction: Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees, ed. Michael Cernea and Christopher McDowell. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Ginsburg, Faye D., Lila Abu-Lughod, and Brian Larkin. 2002. “Introduction: The Social Practice of Media.” Pp. 1–38 in Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain, ed. F.D. Ginsburg, L. Abu-Lughod, and B. Larkin. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hansen, Art. 1992. “Some Insights on African Refugees.” Pp. 100–110 in CORI: Selected Papers on Refugee Issues, ed. P. DeVoe. Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association.

Mahapatra, L.K., and Sheela Mahapatra. 2000. “Social Re-Articulation and Community Regeneration among Resettled Displacees.” Pp. 431–444 in Risks and Reconstruction: Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees, ed. Michael Cernea and Christopher McDowell. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Maldonado, Julie Koppel, Christine Shearer, Robin Bronen, Kristina Peterson, and Heather Lazrus. 2013. “The Impact of Climate Change on Tribal Communities in the US: Displacement, Relocation, and Human Rights.” Climatic Change 120, no. 3: 601–614.

Oliver-Smith, Anthony. 2005. “Communities after Catastrophe: Reconstructing the Material, Reconstituting the Social.” Pp. 45–70 in Community Building in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Stanley E. Hyland. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research.

Oliver-Smith, Anthony. 2009. “Evicted from Eden: Conservation and the Displacement of Indigenous and Traditional Peoples.” Pp. 141–162 in Development and Dispossession, ed. A. Oliver-Smith. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research.

Palacio, Joseph O. 1982. Posthurricane Resettlement in Belize. In Involuntary Migration and Resettlement: The Problems and Responses of Dislocated People. Art Hansen and Anthony Oliver-Smith, Eds. Pp. 121-135. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Rogers, Sarah, and Mark Wang. 2006. “Environmental Resettlement and Social Dis/re-Articulation in Inner Mongolia, China.” Population and Environment 28 (1): 41–68.

Whyte, Kyle Powys. 2014. “Justice Forward: Tribes, Climate Adaptation and Responsibility.” Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples in the United States: Impacts, Experiences and Actions: 9–22.

Wildcat, Daniel R. 2009. Red Alert! Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge. Speaker’s Corner. Golden, Colo.: Fulcrum.

Witter, Rebecca, and Terre Satterfield. 2014. “Invisible Losses and the Logics of Resettlement Compensation.” Conservation Biology 28 (5): 1394–1402.

Cite as: Jessee, Nathan. 2016. “Hope for ‘Just Resilience’ on Earth Day.” EnviroSociety. 22 April. www.envirosociety.org/2016/04/hope-for-just-resilience-on-earth-day.