The “David and Goliath” story Stuart Kirsch tells in Mining Capitalism (2014)—of global underdogs triumphing over a powerful mining company, aided and abetted by Global North activists—is replicated in another story from Papua New Guinea (PNG), albeit concerning a different mine: the Porgera gold mine in the PNG highlands, the country’s second largest mine (Columbia-Harvard 2015: 20). In brief, the Porgera Landowners Association (PLOA) and the Porgera-based Akali Tangi Association (ATA; commonly translated as Human Rights Association), operating in tandem with MiningWatch Canada (MWC),1 pressured Porgera Joint Venture (PJV) to give reparations to women who claimed to have been gang raped by PJV’s security guards. At the time, the Canadian company Barrick Gold Corporation, then regarded as the world’s leading gold mining company, was the majority shareholder. Although Barrick continues to manage the mine, it shares that honor with Zijin, a large Chinese gold company, which bought 50 percent of Barrick’s equity in May 2015.

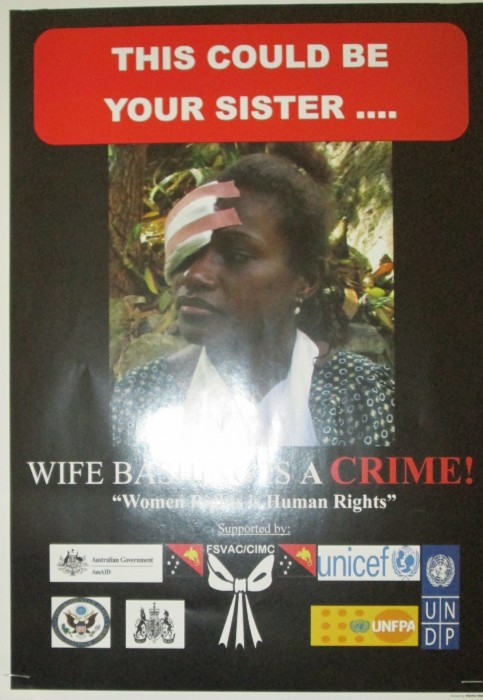

In 2011, Human Rights Watch (HRW), which had investigated the allegations of rape and confirmed some of them, made its report available online (Albin-Lackey 2011). Prodded by the HRW investigation and in light of an investigation by the PNG police, Barrick undertook its own investigation and acknowledged there had indeed been instances of rape by PJV security guards. Barrick then quickly developed a framework for compensating survivors: the Porgera “Remedy Framework” (hereafter, the Framework), the slogan for which was “Olgeta Meri Igat Raits” (“All Women Have Rights”). The process of compensating survivors would be supervised by a Porgera Remedy Framework Association (PRFA). This was headed by two women with impeccable women’s rights credentials: Ume Wainetti, the head of the PNG Family and Sexual Violence Committee, “the leading civil society organization addressing family and sexual violence” in PNG (Barrick 2016: 3); and Dame Carol Kidu, who is largely responsible for important PNG legislation advancing women’s and girls’ rights. Cardno, or Cardno Emerging Markets, “an environmental, social and infrastructure consultancy with substantial [PNG] experience” (3), was hired to implement the Framework’s “remedy mechanism” (Columbia-Harvard 2015: 25).

In designing the Framework, Barrick sought compliance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (hereafter UNGP), which were drafted by John Ruggie—a renowned Harvard University professor in human rights and international affairs and former UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Business and Human Rights—and passed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011. The significance of the UNGP for present purposes lies in their promise of regulating Global North corporations as they operate in the Global South—Barrick, for example. The Framework is among the first efforts worldwide to implement the UNGP, and its successes and failures provide insight into the efficacy of the UNGP as a force for ethical governance in the arena of international business.

The UNGP rest upon “three pillars”: “protect,” which references the state duty of protecting its citizenry; “respect,” which holds corporations responsible for supporting internationally recognized human rights; and “access to a remedy,” which allows for both judicial and nonjudicial remedy mechanisms, as devised by a state and/or a corporation. The Framework falls into the category of a nonjudicial remedy mechanism, or “operational-level grievance mechanism” (OGM; Columbia-Harvard 2015: 28), but one that had an “adjudicative function” (Edono Rights 2016: 45).

How did it work? A list of survivors was generated from the 253 women who stepped forward in response to the “word of mouth” publicity given to the initiative. A Claims Assessment Team within the PRFA (Edono Rights 2016: 4) determined that 137 of these were eligible for reparations. Of these 137, 11 women withdrew to pursue a legal remedy, as discussed below, while another 7 appear to have died before reparations were awarded; 119 women in all received reparations (Columbia-Harvard 2015: 26). The remedy package typically included cash, counseling services, medical costs, and business training, along with school fees in some cases (Edono Rights 2016: 1; Columbia-Harvard 2015: 71). Barrick’s estimate of the average value of the remedy package was 23,630 kina (K), or $9,248.17 (Columbia-Harvard 2015: 71). The figure I was told when talking to one of the 119 awardees in July 2015 was K20,000, roughly $8,000.

Eleven women refused the package and sought counsel from EarthRights International (ERI), a US-based NGO that offers legal assistance to people seeking to defend the environment and human rights. With the assistance of ERI, these women threatened to sue Barrick, and a package deal reportedly worth K200,000, about ten times what the majority of claimants had received, was negotiated (Columbia-Harvard 2015: 72). Once those who had received the smaller package got wind of the larger package, they staged “a large public protest, during which police were reportedly called” (50) and petitioned the PRFA for further compensation. In response Barrick offered another K30,000 (78), bringing the total award for the majority of complainants to around K50,000, a mere 25 percent of the K200,000 target. Many survivors now demand the full sum of K200,000, but Barrick refuses to offer further compensation (72–73, 77–78).

“Righting Wrongs” is a report prepared by Columbia Law School’s Human Rights Clinic and Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic, the mission of which is to advance human rights globally. Based on a three-year investigation of the Framework, the Columbia-Harvard report found that the process fell short of international standards for remedying human rights violations. Among the Framework’s key flaws were that: 1) its scope was narrowed to sexual assault, “despite longstanding allegations of non-sexual assaults by mine staff” (Columbia-Harvard 2015: 4); 2) claimants had to sign a document foreswearing legal action against the company as a condition of receiving reparations; 3) the process was designed with inadequate input from claimants and communities; 4) the remedy opportunity the Framework offered was not sufficiently publicized to attract all possible claimants; 5) the measures taken to protect the privacy of claimants were inadequate, creating security risks for them; and 6) the level of reparation varied but not according to degree of suffering, suggesting that the reparations were “inequitable or arbitrary” (5), to the dissatisfaction of most recipients.

An alarming aspect of the Framework process was the degree to which it functioned independently of state justice institutions. The Framework, a “non-judicial” OGM evaluated claimants “largely on their own accounts, as opposed to having to confront alleged abusers in proceedings” (Columbia-Harvard 2015: 54). PJV had conducted its own internal investigations of sexual assaults in 2010 and 2011, resulting in fourteen firings, and urged police to pursue its own inquiries. As a result, four arrests were made but no convictions (74, 85). As the Columbia-Harvard report notes, “[a] private actor mechanism alone cannot fulfill all elements of an individual’s right to remedy because it cannot undertake criminal sanctions” (74), which the state alone can undertake. The Columbia-Harvard report correctly notes that in PNG “most crimes of sexual violence are unreported and those that are reported rarely result in prosecutions” (86)—sexual offenders acting with impunity despite the existence of PNG laws sanctioning sexual assault and rape.

The Framework did little to disrupt a status quo that many find intolerable. Under the UNGP, companies are expected to cooperate fully with police and prosecutors and to hand over any relevant evidence, thus complementing rather than supplanting state judicial processes (70), the first “pillar” of the UNGP. The requirement to cooperate with the police is meaningless if survivors fail to report the rape. Like women elsewhere in the western Pacific, Porgeran women were for the most part reluctant to approach the police lest their victimhood be revealed. What fell short here were the UNGP themselves, which functioned in this instance to endorse a nonjudicial remedy for criminal activity. As per the status quo, law enforcement was largely circumvented, furthering the impunity PNG sexual predators typically enjoy.2

Two further disturbing aspects of the Framework’s impact: claimants were indeed stigmatized once it became known that they were rape victims, and they were unable to hold onto the compensatory cash they had received. A second evaluation of the Framework, this one commissioned by Barrick, was undertaken by Enodo Rights, a designer of “cutting-edge corporate human rights strategy.” Of the sixty-two recipients of Framework reparations Enodo Rights interviewed: “[m]ost were threatened and physically abused by men in their family to give up much of the compensation. Many were left with nothing…their families assaulted them, their money was taken, their husbands left them, and they are pariahs in their community” (Edono Rights 2016: 5). Similarly, according to the Columbia-Harvard report, some claimants were “threatened or physically harmed by family members, often husbands” in response to the revelation of rape victimhood and/or because they wanted the money their spouse or kinswoman had received (2015: 65). From Barrick’s perspective, the goal it sought to achieve—”to provide ’empower[ing] and durable’ remedies and protect claimants from further harms” (Barrick 2016: 2)—was not met, a finding Barrick finds “deeply” disturbing (1–2).

To return to Kirsch’s point: Davids can indeed triumph over Goliaths in a world in which human rights activists and NGOs provide support and guidance to global underdogs. In this case, the Porgera Alliance, supported by MiningWatch Canada and Human Rights Watch, successfully pressured PJV to acknowledge the transgressions of its security guards, the upshot being the development of a nonjudicial mechanism for delivering reparations to survivors—a victory to be applauded. But David and Goliath were both males, and the David and Goliath scenario reveals nothing of the gender politics that might come into play in actual instances of global–local showdown. Looking beyond Northern–Southern class-based tussles to gender, then, the Porgera case tells us this: UNGP-inspired remedies are necessarily pursued in situ, with respect to entitlement regimes that may or may not rest upon the principle olgeta meri igat raits. Where women are considered less important than, even inferior to, men, as the reporting on PNG highlands societies overwhelmingly suggests, local perspectives antithetical to human rights ideology may ultimately hijack rights-based projects (see Biersack et al.).

Aletta Biersack is an anthropology professor at the University of Oregon and has conducted long-term research among the Ipili speakers of the Porgera and Paiela valleys. Her research interests include feminist political ecology and the dynamics of globalization, especially as related to mining and attempts to transfer human rights ideology across cultural boundaries.

Notes

1. See MWC’s discussion in MWC and RAID 2014.

2. The Columbia-Harvard report does touch on this problem: “Some human rights and criminal justice experts have expressed concern that mechanisms like this might undermine the development of criminal cases around these instances of violence as well as the criminal justice system more generally” (2015: 87). The Enodo Rights assessment casts this problem in a different light: “The Framework would serve a quasi-judicial role for vulnerable women whose access to justice before courts was virtually non-existent” (2016: 2–3).

References

Albin-Lackey, Chris. 2011. “Gold’s Costly Dividend: Human Rights Impacts of Papua New Guinea’s Porgera Gold Mine.” New York: Human Rights Watch.

Barrick Gold Corporation. 2016. Response to Enodo Rights’ “Pillar III on the Ground: An Independent Assessment of the Porgera Remedy Framework.” 19 January.

Biersack, Aletta, Margaret Jolly, Martha Macintyre, eds. Under review. Gender Violence and Human Rights: The Search for Justice in Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu. Canberra: Australian National University.

Columbia Law School Human Rights Clinic and Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic (Columbia-Harvard). 2015. “Righting Wrongs? Barrick Gold’s Remedy Mechanism for Sexual Violence in Papua New Guinea: Key Concerns and Lessons Learned.”

Enodo Rights. 2016. “Pillar III on the Ground: An Independent Assessment of the Porgera Remedy Framework.”

Kirsch, Stuart. 2014. Mining Capitalism: The Relationship Between Corporations and Their Critics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

MiningWatch Canada and RAID. 2014. “Privatized Remedy and Human Rights: Re-thinking Project-Level Grievance Mechanisms.” Paper delivered at the third annual UN Forum on Business and Human Rights, Geneva, 1 December.

Porgera Joint Venture (PJV). 2014. “Remedy Framework: Olgeta Meri Igat Raits (‘All Women Have Rights’).” Toronto: Barrick Gold Corporation.

Porgera Joint Venture (PJV). 2013. “Olgeta Meri Igat Raits (‘All Women Have Rights’) Individual Reparations Program: Claims Process Procedures Manual.” Toronto: Barrick Gold Corporation.

Cite as: Biersack, Aletta. 2016. “Olgeta Meri Igat Raits? (All Women Have Rights?)” EnviroSociety. 29 January. www.envirosociety.com/2016/01/olgeta-meri-igat-raits-all-women-have-rights.