In April 2015, the rains stopped coming to the New Guinea Highlands—a result of the current El Niño impacting the planet. A few months later in August, the inevitable frosts arrived that also accompany El Niños. What few crops were struggling to survive in people’s gardens were utterly decimated by the frosts, for while people garden in the highlands up to 2,800 meters above sea level, the crops they grow are mostly adapted to lowland tropical environments. The staples of the highlands—sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) and taro (Colocasia esculenta)—cannot be stored; therefore, the inability to continually plant and harvest staple crops poses food insecurity for almost 2 million people in Papua New Guinea (PNG).

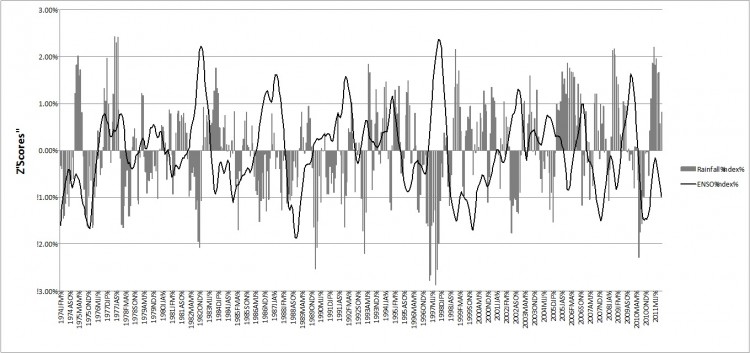

El Niños are one-half of a larger phenomenon known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. While the El Niño refers to a rise in sea surface temperatures in the Eastern Pacific, the Southern Oscillation tracks a rise in high atmospheric pressure in the Western Pacific. Together, ENSO creates dry conditions with clear, cold nights that bring frosts to as low as 1,600 meters above sea level. Just how strong does an ENSO have to be though to cause droughts and frosts in highlands PNG? To understand this question, I was able to access monthly precipitation data from 1974 to 2011 for my field site in the Porgera Valley in the western Enga Province from environmental records from Barrick Gold, the operator of the Porgera Gold Mine. From this data, I created a rainfall index using standardized Z-scores based on a three-month running mean (the same method used to calculate the ENSO index). I then overlaid the rainfall index from Porgera onto the ENSO index developed by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

As seen in the figure above, strong El Niños (typically above 1.75 standard deviations from the mean) result in severe droughts in the western Enga Province. So far this year, the ENSO index has climbed from 0.5 to 1.7 over the past seven months, signaling the potential for the onset of a strong El Niño.

Papua New Guinea highlanders are not strangers to ENSO-caused droughts and frosts (Allen 1989; Brown and Powell 1974; Ellis 2003; Jacka 2015; Waddell 1975). Approximately every twenty years or so (1971–72, 1997–98, and the present), a major El Niño event has occurred in the highlands precipitating a number of customary institutional practices to mitigate the impacts of water scarcity and food insecurity in affected communities. These responses range from dispersing garden plots in the local area to large-scale migration into lower altitude areas. During the El Niño in 1971 and 1972, the Australian colonial government, churches, and NGOs discouraged migration to more effectively deliver food aid, which was ultimately insufficient, thereby worsening conditions for thousands of people. In 1997 and 1998, the PNG government again failed to provide sufficient promised food aid. The national response to this El Niño, so far, looks like a repeat of the events of 1997 and 1998, albeit PNG has a fairly widespread mobile phone service, so it will be interesting to understand the role of mobile communications in shaping people’s responses to food and water insecurities.

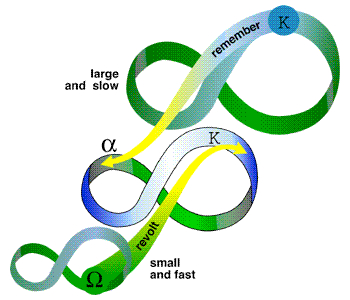

As an environmental anthropologist, I wondered how an anthropological focus could better help us to both theoretically study the effects of El Niño on people’s livelihoods while simultaneously contributing research that can help to mitigate the impacts of global climatic changes that more and more subsistence-based peoples will be experiencing in the coming decades. Most importantly, anthropologists need to do more than just document socio-environmental disasters. One way forward in terms of theorizing responses to extreme events is to use a framework derived from studies of resilience and adaptive capacity. In their edited volume, Panarchy, Gunderson and Holling (2002) provided a framework for how to integrate the social dimension into studies of resilience. They proposed a heuristic they called the adaptive cycle as a way to think about the relationships between stasis and change in systems. In essence, systems move through four phases: a period of exponential change (r), a period of growing stasis (K), a period of readjustment or collapse (W), and a period of reorganization (a). The important point is that, as Carl Folke has noted, “instabilities organize the behaviors [of systems] as much as do stabilities” (2006: 258). Slow and gradual changes thereby complement rapid transitions and disturbances; moreover, resilience fluctuates throughout the cycle. A panarchy in their conceptualization is a nested set of adaptive cycles operating at different temporal and spatial scales. Smaller-scale, faster dynamics disrupt and transform systems, while larger-scale and slower dynamics stabilize systems and build resilience. An ecological example is of a fire burning a forest (a small-scale, rapid dynamic), yet the seed bank in the soil (a larger-scale, long-term dynamic) allows the forest to regrow and renew itself.

Applying the concept of a panarchy to a social system, Holling and colleagues explore the relationships between “slowly developed myths,” “faster rules and norms,” and “still faster processes to allocate resources” (2002b: 72). While “slower levels constrain the behavior of faster levels,” it is critical to recognize that “the attributes of the slower levels emerge from the experience of the faster” (ibid.). Critically, though, as Folke argues, “Resilience is not only about being persistent or robust to disturbance. It is also about the opportunities that disturbance opens up in terms of recombination of evolved structures and processes, renewal of the system and emergence of new trajectories. In this sense resilience provides adaptive capacity” (2006: 259).

I was recently awarded a RAPID grant from the National Science Foundation to examine the processes that foster social-ecological resilience in the face of global climatic changes. To paraphrase the summary of the award:

Resilience research has found that the capacity of a system to withstand shocks and uncertainties is a property of a system’s overall resilience, not just the resilience of the specific component under stress. Some aspects of a social-ecological system, such as cultural worldviews, are more resistant to change and change more slowly than other aspects, such as rules and norms, which change more quickly. Surprisingly, while systems for allocating resources generally change fastest of all, little is known about how this actually happens and how the changes work their way through the system as a whole to finally affect rules, norms, and worldviews. At a time when resources throughout the world are increasingly under stress from war, population movement, and natural disasters, it is critical for policy makers and citizens, as well as researchers, to understand the social processes through which resource reallocation is achieved when a social-ecological system is under stress.

I will be in Enga Province in January 2016 to examine the small, fast decisions people are making about resource allocation and management in the midst of an El Niño. I will then return in May and June after the El Niño has ended to conduct follow-up research regarding what people think worked and what didn’t. In addition to interviews, I will be conducting participatory risk ranking exercises and concept mapping of successful mitigation and adaptation strategies. Finally, I will assess the role of state and multinational corporations in helping people to cope with severe crises. However, with mining suspended in Porgera due to the drought, determining what role multinationals play in mitigating disasters is open to question.

Climate change threatens multiple nations throughout the southwestern Pacific. With the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference coinciding with the current El Niño, we can only hope that world leaders will take the steps necessary to resolve the continuing anthropogenic forcing of global climate change. Meanwhile, environmental anthropologists can work to understand, theoretically and practically, responses that subsistence-based peoples are taking in an era of increasingly severe climatic changes to highlight social-ecological resilience.

Dr. Jerry K. Jacka is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder. His book Alchemy in the Rain Forest: Politics, Ecology, and Resilience in a New Guinea Mining Area (Duke University Press, 2015) draws on theories of political ecology, place, and ontology and ethnographic, ecological, and spatial methods to examine the making of a resource frontier in the Porgera Valley, PNG. His work has been supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research and the National Science Foundation.

References

Allen, Bryant. 1989. “Frost and Drought through Time and Space, Part I: The Climatological Record.” Mountain Research and Development 9, no. 3: 252–278.

Brown, Mary, and J.M. Powell. 1974. “Frost and Drought in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea.” Journal of Tropical Geography 38: 1–6.

Ellis, David M. 2003. “Changing Earth and Sky: Movement, Environmental Variability, and Responses to El Niño in the Pio-Tura Region of Papua New Guinea.” Pp. 161–180 in Weather, Climate, Culture, ed. S. Strauss and B. Orlove. Oxford: Berg.

Folke, Carl. 2006. “Resilience: The Emergence of a Perspective for Social-ecological Systems Analyses.” Global Environmental Change 16: 253–267.

Gunderson, Lance, and C. S. Holling, eds. 2002. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Holling, C. S., Lance Gunderson, and Garry D. Peterson. 2002. “Sustainability and Panarchies.” Pp. 63–102 in Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems, ed. L. Gunderson and C.S. Holling. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Jacka, Jerry K. 2015. Alchemy in the Rain Forest: Politics, Ecology, and Resilience in a New Guinea Mining Area. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Waddell, Eric. 1975. “How the Enga Cope with Frost: Responses to Climatic Perturbations in the Central Highlands of New Guinea. Human Ecology 3, no. 4: 249–273.

Cite as: Jacka, Jerry K. 2015. “Socio-Environmental Disasters and Resilience Approaches.” EnviroSociety. 30 November. www.envirosociety.org/2015/11/socio-environmental-disasters-and-resilience-approaches.