In November 2014, Madagascar was hit by a major outbreak of bubonic plague. Its epicenter was in Amparafaravola, a midsize town with a hospital staff that was caught off guard. Public outreach was slow and disorganized, dispensaries were understocked with antibiotics, and people did not believe the new fever was the actual plague … until several deaths occurred.

The evolution of the disease into the more lethal pneumonic variety risked a cataclysmic rise in mortalities. Health-care providers feared it would spread like wildfire into the capital, Antananarivo, where it has long existed at low-grade levels, especially within prisoner and homeless populations.

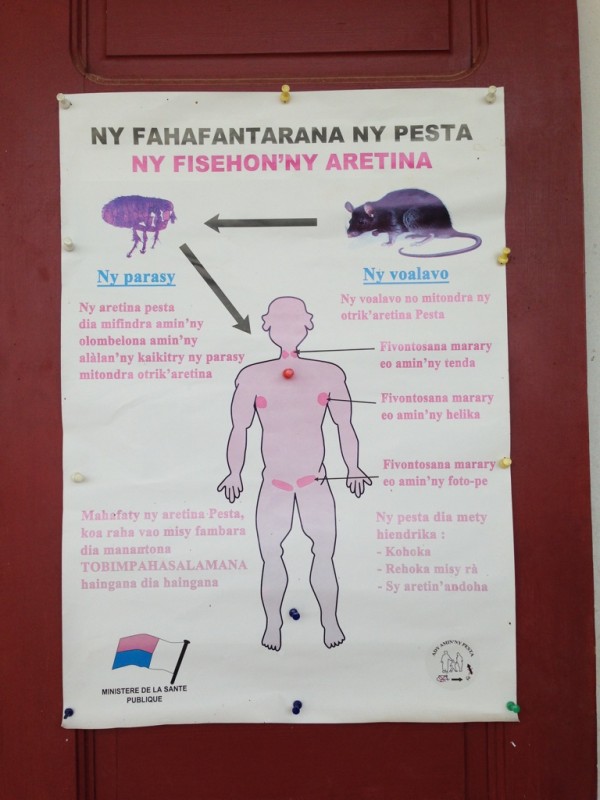

Poster about plague symptoms at the hospital of Amparafaravola

A poor health-care delivery system coupled with people’s lack of knowledge about the disease means that most plague victims do not seek treatment in time. Last year’s epidemic in Madagascar did in fact reach the capital, but fortunately, it did not kill at the rate feared.

The bubonic plague is one of those ancient diseases that people assume has gone the way of leech cures. But it still exists around the world, including the western United States, where rodents such as mice, ground squirrels, rock squirrels, and prairie dogs can carry the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Although human infection in the US is rare, it sometimes happens. When it does, the disease, if caught early enough, is easily knocked out with antibiotics.

In Madagascar and other poor nations, however, the bubonic plague remains endemic, about two thousand cases reported per year. The disease is kept alive by its rat hosts that carry the vector, the common flea. People who survive the plague are left in a weakened state for months, as I learned from a young man in Amparafaravola who recalled what he believed to be the precise moment of his infection: he was standing in a narrow, trash-strewn alley between the back of his house and a storage room filled with unhulled rice, when he felt the bite of a flea on the back of his neck. Soon after, he had a fever and swollen lymph nodes.

The alley where a flea bit a man who then got the plague

Zoonoses, diseases that spill over from nonhuman to human populations, have always been intrinsic to human evolution, but they are becoming more frequent due to climate change and habitat perturbation. The plague is one of the nastier zoonotic diseases infecting people and animals on the island. Some others include Rift Valley fever virus, leptospirosis, intestinal parasites, dengue, chikungunya, and rabies. In Madagascar, zoonoses thrive in settlements near primary rain forest, fragments of which are dwindling rapidly thanks to the mining and logging boom of the past decade.

Novel viruses often lurk at the boundaries of rain forest and settlements, infecting people frequently but not gaining a sturdy foothold in human populations until reaching a certain threshold. This “viral chatter” of the human–wildlife interface can alert scientists to emergent zoonoses and anthropozoonoses (human-to-animal disease). Anthropologists have an important role in studying the kinds of human–animal interactions and political ecologies that jeopardize the health of multispecies communities.

Environmental change often creates conditions that trigger the proliferation of microorganisms, many of which are pathogenic to higher-order species. The changing “landscape of disease” demands an ecological perspective of disease and an interdisciplinary approach to solving zoonoses, as reflected by the One Health Initiative.

For anthropologists, the study of zoonosis calls for disciplinary spillover of epidemiology and multispecies ethnography, as well as the cross-fertilization of environmental and medical anthropology. It involves tracking down disease pathways in people’s daily lives and imagination, and investigating scientific and folk etiologies. It calls for attentiveness to the elements of disease “hotspots,” such as power and population dynamics, economic activity, habitat change, and risky human–animal transactions, all of which enable us to grasp how zoonotic diseases emerge, spread, and run their courses in stratified social settings. Anthropologists can also contribute the fine-grained accounts of people’s lived experiences of disease that often evade the data captured by epidemiological surveys.

I made a short trip to Madagascar in June 2015 to begin a new project on zoonosis and land degradation in rural, urban, and peri-urban contexts. My first arena of investigation centers on the relationship between mining, biodiversity offsetting, and zoonosis. One of my field sites is Moramanga, a town located beside a large nickel and cobalt mine and its biodiversity offset. The mining company advocates environmental sustainability—the protection of biodiversity, in particular—as it pursues extractive activities that alter the soil substrate, the biological composition of habitats, the settlement and livelihood patterns of Malagasy inhabitants, and the dynamics of pathogens in the environment.

I have started to investigate the ways residents of Moramanga interpret their quality of life in relation to the mine, particularly in light of the mine’s looming presence in the town as environmental manager and development agency. Moramanga is also the site of a satellite office of the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar, which is involved in a number of health programs, including efforts to control zoonotic diseases like the plague and rabies. In Moramanga, I’m focusing on rabies, and my preliminary investigations have yielded some interesting finds.

What does rabies have to do with the mine? There’s no obvious relationship. However, the mine has employed hundreds of people and has subsidized housing for relocated employees, who in turn acquire dogs to guard their properties. The growing population of mean dogs has, according to some, exacerbated the spread of rabies in town. Dog bites are certainly frequent. At the hospital, the rabies ward receives about four cases daily of people bitten by dogs and in need of a rabies vaccine.

In Moramanga, as in the pestilent districts, people wonder about the origins of disease outbreaks and tend to locate origin points beyond the limits of their own towns. Although people understand that flea-infested rats, in the case of plague, and pet dogs and cats, in the case of rabies, transmit these diseases to humans, people ask, “Why here, why now?” When and where did it begin?

Boy receiving the rabies vaccine after being bitten by a dog

These kinds of etiological mysteries produce some fascinating theories. I think an important part of my project will involve chasing down folk etiologies. Although they reveal a sometimes shaky grasp of medical science, which health-care researchers worry about, such stories also illuminate how people perceive disease context—how they interpret the effects of broken service systems and state–private enterprise collusions that affect urban and rural ecosystems alike.

How the plague-carrying rats come in contact with people has to do with flooding during the rainy season, with a failed garbage collection system in Madagascar’s cities and with the cycles of agriculture that bring people closer to the vegetal havens of the rodents at certain times of the year. People also think the plague outbreaks have a lot to do with corruption in the capital: the officials sell the diesel fuel meant for garbage trucks, therefore preventing them from making their rounds. Garbage piles up in different sections of the city, and rats, the plague’s hosts, proliferate.

Rat cages distributed during the plague epidemic in Amparafaravola

In Moramanga, doctors and everyday people alike believe rabies comes from a species of wild dog called a kelibetratra (“little big chest”), which looks something like a pit bull with small limbs and a large chest. The kelibetratra, always rabid (romotra), comes out of the rain forest, attacks domesticated dogs, and infects them. The strange thing is that no species of wild dog actually exists in Madagascar, and the kelibetratra, like a werewolf whose body is never seen, only its carnage, is also thought to roam around neighborhoods of the capital, emerging at night as people sleep and getting in vicious dogfights. In Moramanga, the kelibetratra tells us something about etiological beliefs, as well as beliefs about how forest erosion is scaring out dangerous animals.

Stories such as these, which blend cryptozoology and political critique, can offer important insights to medical practitioners interested in resolving zoonotic outbreaks. They shed light on the imagined pathways of disease, pathways that crisscross the material landscapes of rampant resource extraction and dysfunctional government services.

Genese Marie Sodikoff is an Associate Professor of Anthropology and Chair of Sociology and Anthropology at Rutgers University, Newark. She has done fieldwork in Madagascar, focusing on low-wage labor and forest conservation, and more recently on biotic and cultural extinctions. She is currently pursuing training in epidemiology, supported by a Mellon New Directions Fellowship, for a new book project about land degradation and zoonosis in Madagascar.

All photographs in this post are credited to the author.

Cite as: Sodikoff, Genese Marie. 2015. “Spillover Anthropology: Multispecies Epidemiology and Ethnography.” EnviroSociety. 5 August. www.envirosociety.org/2015/08/spillover-anthropology-multispecies-epidemiology-and-ethnography.